“Un’opera d’arte per divenire immortale deve sempre superare i limiti dell’umano senza preoccuparsi né del buon senso né della logica”. Giorgio de Chirico

Giorgio De Chirico è nato a Volos, in Grecia, il 10 luglio 1888 da genitori appartenenti a famiglie nobili italiane; il padre Evaristo, barone palermitano, è un ingegnere ferroviario e si trova in Grecia per progettare la nuova ferrovia, la madre è la baronessa genovese Gemma Cervetto.

Alla morte del padre, nel 1905, Giorgio De Chirico insieme alla madre e al fratello Andrea (che poi assumerà il nome d’arte Alberto Savinio) si sposta a Monaco di Baviera, dove viene in contatto con la pittura simbolista e mitologica di Arnold Böcklin, secondo il quale lo scopo dell’arte è quello di rivelare con un linguaggio non più logico, l’altra realtà che supera l’uso dei sensi e della ragione, esplorando la profondità psichica con un utilizzo accorto di “simboli”.

Durante la prima guerra mondiale, De Chirico si arruola volontario e viene mandato a Ferrara con l’incarico di scritturale, proprio in quel periodo conosce Carrà (*) e De Pisis. Il primo impatto con Ferrara non fu dei migliori, egli stesso scrisse: “Partivo per Ferrara, partivo per quella città che Burckhardt definì la più moderna d’Europa e che a me si rivelò come la città più profonda, più strana e più solitaria della terra”. Rimase a Ferrara tre anni e mezzo e piano piano la città gli entrò profondamente nell’anima, il paesaggio ferrarese si rivelò essenziale per la sua pittura metafisica.

De Chirico si sposta anche a Torino, a Milano, a Parigi, a New York, è poliglotta: parla italiano, tedesco, greco, francese, inglese, ma questo suo viaggiare lo porta a sentirsi sradicato, apolide.

Di sé stesso dice: “I had many houses but never a home” (ho avuto tante abitazioni ma mai una casa).

Definisce la sua famiglia una famiglia di centauri ma percepisce che sia lui che il fratello sono come due argonauti, che, dopo la partenza dalla Grecia, si muovono per l’Europa senza una meta precisa. Questo non sentire le proprie radici sarà la spinta verso il periodo metafisico e nonostante non torni più in Grecia per tutto il resto della sua vita, l’impronta classica emerge in ogni suo dipinto.

Su queste vicende de Chirico costruisce una sorta di mitologia familiare che permea tutta la sua opera e i cui segni compongono tante volte il rebus, l’enigma. Il centauro e la locomotiva sono la memoria del padre scomparso, ingegnere ferroviario in Tessaglia. Le vele a simboleggiare la partenza dei due Dioscuri Giorgio e Andrea.

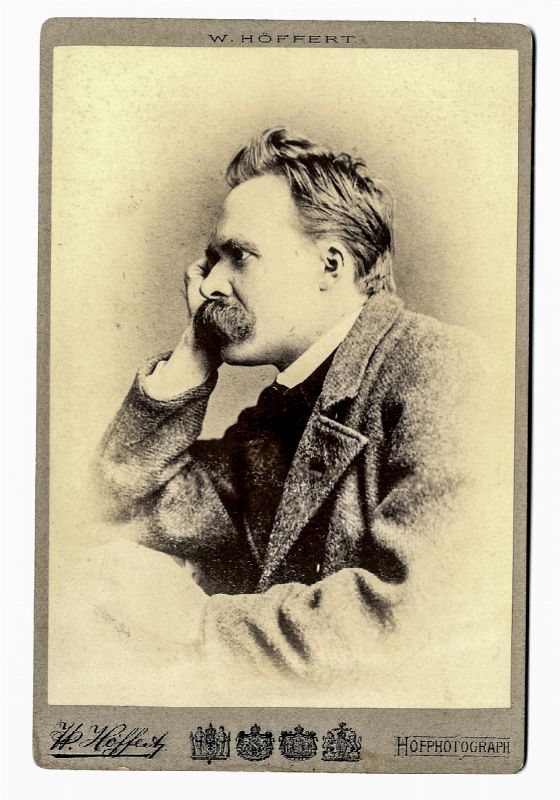

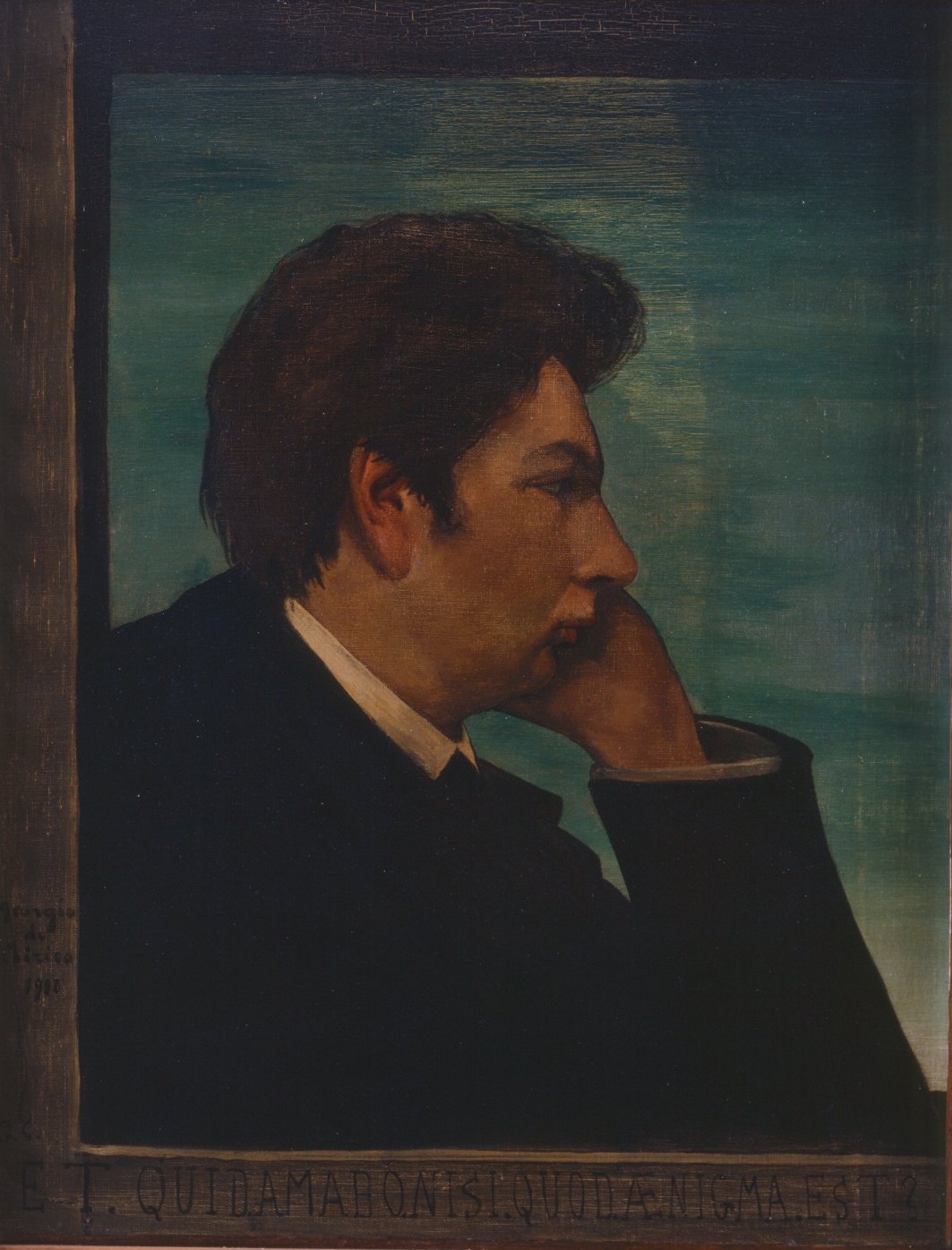

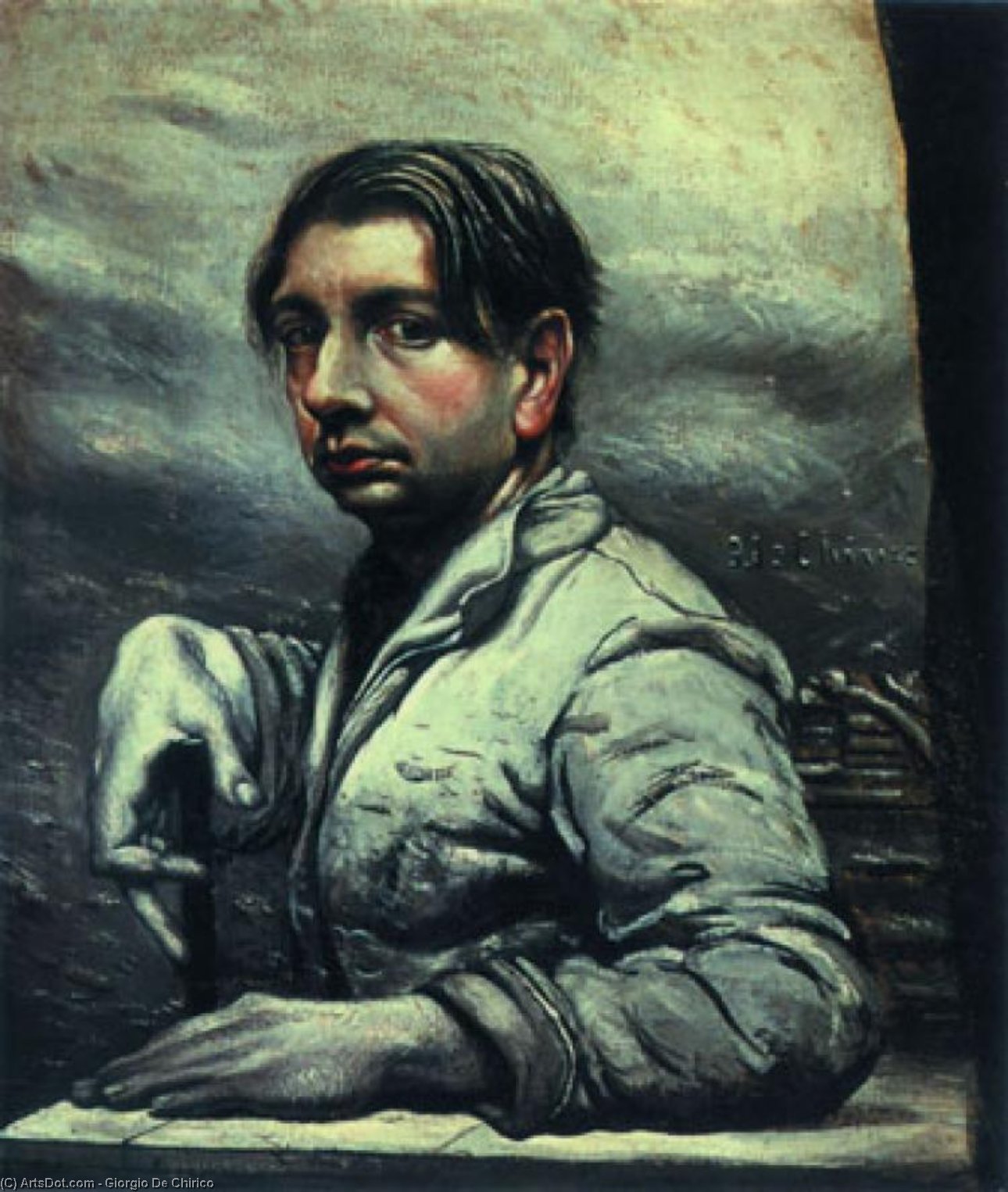

De Chirico ama la filosofia di Schopenahuer ma soprattutto è affascinato dalla filosofia di Nietzsche. E proprio ad una fotografia del 1882 di Nietzsche che si ispira per il suo primo autoritratto, nel 1911 dove non solo si dipinge nella stessa posa del grande filosofo tedesco, ma, con il braccio appoggiato ad una finestra, inserisce all’interno del quadro una cornice dipinta, rimandi evidenti alla pittura rinascimentale italiana, sulla quale è presente una citazione in latino: “Et quod amabo nisi quod aenigma est?” (cosa dovrei amare se non l’enigma?). Il tema dell’enigma sarà centrale nella pittura di De Chirico, esattamente come era stato fondamentale nel pensiero di Nietzsche, che aveva dato il titolo di La visione e l’enigma ad uno dei capitoli più importanti del suo Così parlò Zarathustra.

The exhibition of De Chirico returns to Milan, at Palazzo Reale, featuring a collection of 100 works from the most important international galleries and museums.

“An artwork to become immortal must always surpass the limits of the human, without concern for either common sense or logic.” – Giorgio de Chirico

Giorgio De Chirico was born in Volos, Greece, on July 10, 1888, to parents from noble Italian families; his father, Evaristo, a baron from Palermo, was a railway engineer who was in Greece to design the new railway, and his mother was the Genoese baroness Gemma Cervetto.

After the death of his father in 1905, Giorgio De Chirico, along with his mother and brother Andrea (who later adopted the artistic name Alberto Savinio), moved to Munich. There, he came into contact with the symbolist and mythological painting of Arnold Böcklin, who believed that the purpose of art was to reveal, through a non-logical language, the other reality that surpasses the use of the senses and reason, exploring the depths of the psyche with a careful use of “symbols.”

During World War I, De Chirico enlisted voluntarily and was stationed in Ferrara, where he worked as a scribe. It was during this time that he met Carrà (*) and De Pisis. His initial experience in Ferrara wasn’t the best; he wrote: “I left for Ferrara, a city that Burckhardt described as the most modern in Europe and which revealed itself to me as the deepest, strangest, and loneliest city on earth.” He stayed in Ferrara for three and a half years, and gradually, the city became deeply ingrained in his soul, with the Ferrara landscape becoming essential to his metaphysical painting.

De Chirico also moved to Turin, Milan, Paris, and New York. He was multilingual, speaking Italian, German, Greek, French, and English, but his constant traveling left him feeling uprooted, stateless.

He said of himself: “I had many houses but never a home.”

He described his family as a family of centaurs, but he felt both he and his brother were like two Argonauts, moving through Europe after leaving Greece without a specific destination. This lack of feeling rooted would lead him to his metaphysical period, and despite never returning to Greece for the rest of his life, the classical imprint emerged in every one of his paintings.

De Chirico constructed a sort of family mythology around these events, which permeates his entire body of work and often composes the rebus, the enigma. The centaur and the locomotive serve as memories of his deceased father, a railway engineer in Thessaly. The sails symbolize the departure of the two Dioscuri, Giorgio and Andrea.

De Chirico admired the philosophy of Schopenhauer, but he was particularly fascinated by Nietzsche’s philosophy. His first self-portrait in 1911 was inspired by a photograph of Nietzsche from 1882. Not only did he paint himself in the same pose as the great German philosopher, but he also inserted a painted frame into the artwork, with his arm resting on a window. This referred to the Italian Renaissance painting and contained a Latin quote: “Et quod amabo nisi quod aenigma est?” (What should I love if not the enigma?). The theme of the enigma would become central in De Chirico’s painting, just as it had been crucial in Nietzsche’s thought. Nietzsche had titled one of the most important chapters of “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” as “The Vision and the Enigma.”

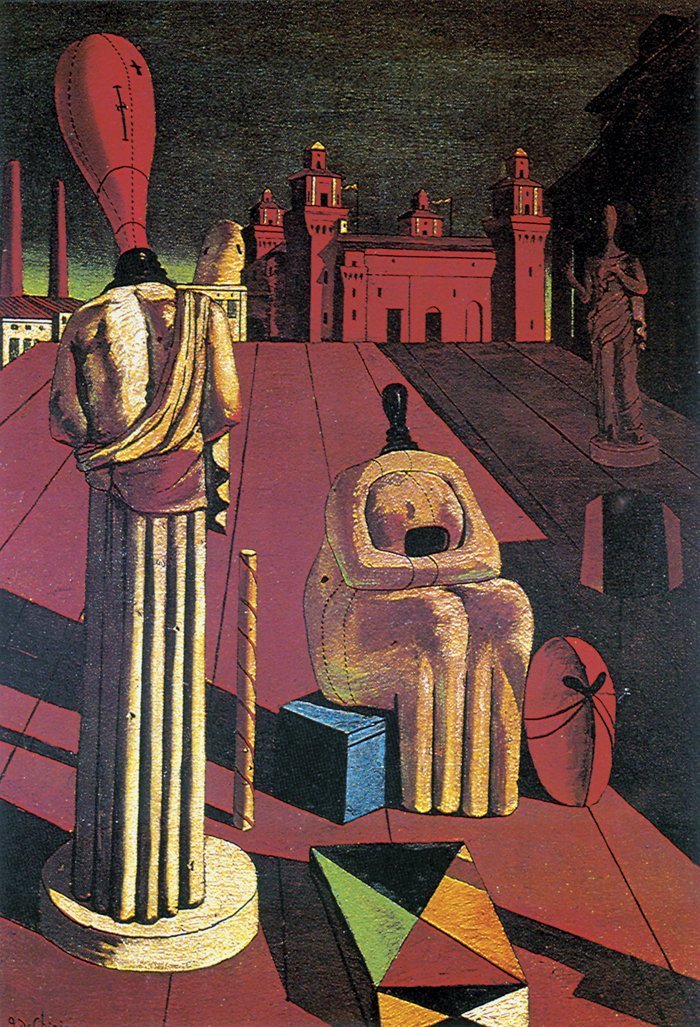

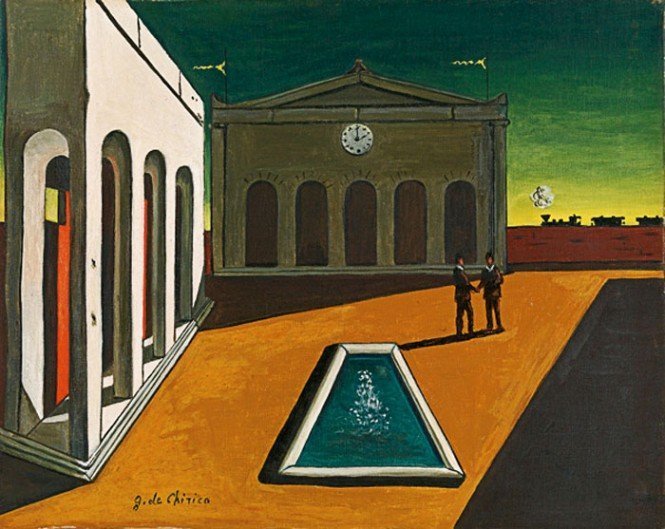

De Chirico si mette in parallelo con Nietzsche, la sua pittura, che non è rivoluzionaria dal punto di vista tecnico, nasce dalla memoria di architetture classiche, le sue composizioni si riconoscono per l’accostamento di figure e oggetti indecifrabili, assemblati in modo nuovo che travolgono l’osservatore ponendolo davanti a immagini inconsuete che rimandano a una realtà inafferrabile.

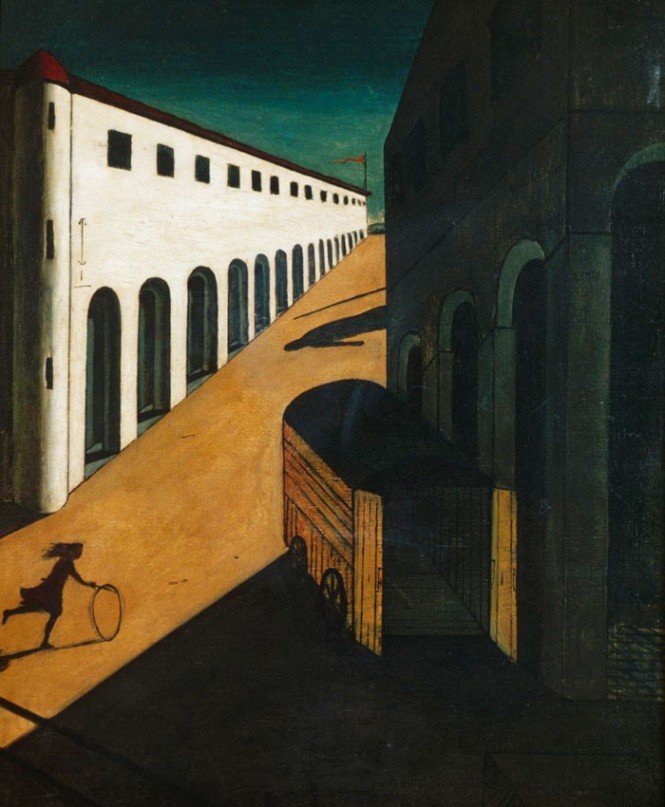

I temi ricorrenti della sua pittura sono quelli dell’infinito, della solitudine, del mistero, dell’enigma, sono le vie deserte e le piazze silenziose, le ombre e le statue il tutto racchiuso in un tempo sospeso di attesa e di presagio.

De Chirico interpreta l’arte come una sorta di continuo confronto tra persone appartenenti a epoche diverse ma che, attraverso la pittura, dialogano in un eterno presente.

Pur frequentando le avanguardie dell’epoca, De Chirico ne resta estraneo, sente di non appartenere a nessun movimento che sia futurista, cubista o iperrealista. I suoi treni sono immobili, al contrario dell’accelerazione futurista e, pur apprezzando Picasso, le sue figure non cercano la scomposizione cubista. De Chirico scompone la realtà, quella sì.

De Chirico aligns himself with Nietzsche; his painting, while not revolutionary from a technical standpoint, emerges from memories of classical architecture. His compositions are recognized for the juxtaposition of indecipherable figures and objects, assembled in a novel way that overwhelms the observer, presenting them with unfamiliar images that allude to an elusive reality.

The recurring themes in his painting are those of the infinite, solitude, mystery, and enigma. They are deserted streets and silent squares, shadows and statues, all enclosed within a suspended time of anticipation and foreboding.

De Chirico interprets art as a continuous dialogue between individuals from different eras who, through painting, converse in an eternal present.

Despite engaging with the avant-garde movements of his time, De Chirico remains distant from them. He feels he doesn’t belong to any movement, whether futurist, cubist, or hyperrealist. His trains are stationary, contrary to the Futurist acceleration, and while he appreciates Picasso, his figures do not seek Cubist decomposition. De Chirico decomposes reality itself.

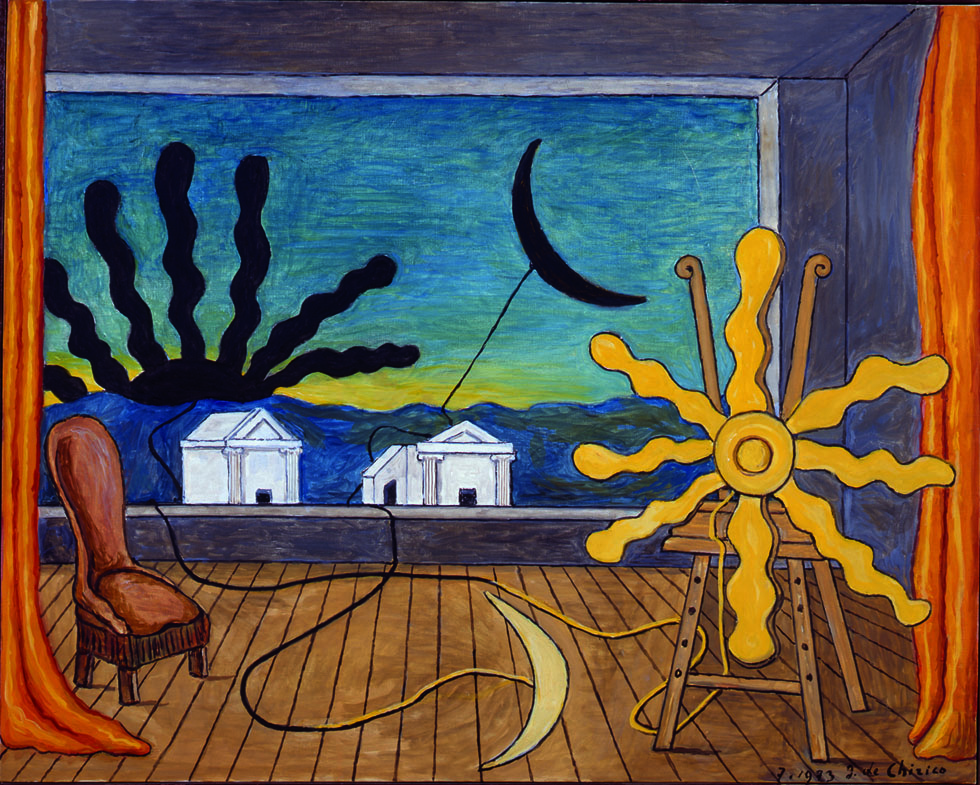

Il mondo di De Chirico è fatto da elementi che riconosciamo in quanto parte del nostro patrimonio culturale, uniti tra di loro in un modo nuovo, con una grammatica diversa che crea l’enigma. Pur utilizzando oggetti reali (statue, manichini, squadre, colonne, monumenti famosi) De Chirico li scompone con un’analisi assoluta, facendoci entrare nel suo mondo onirico e visionario, il suo racconto intimo si snoda tramite le forme, le prospettive e i colori che mutua dalla pittura classica.

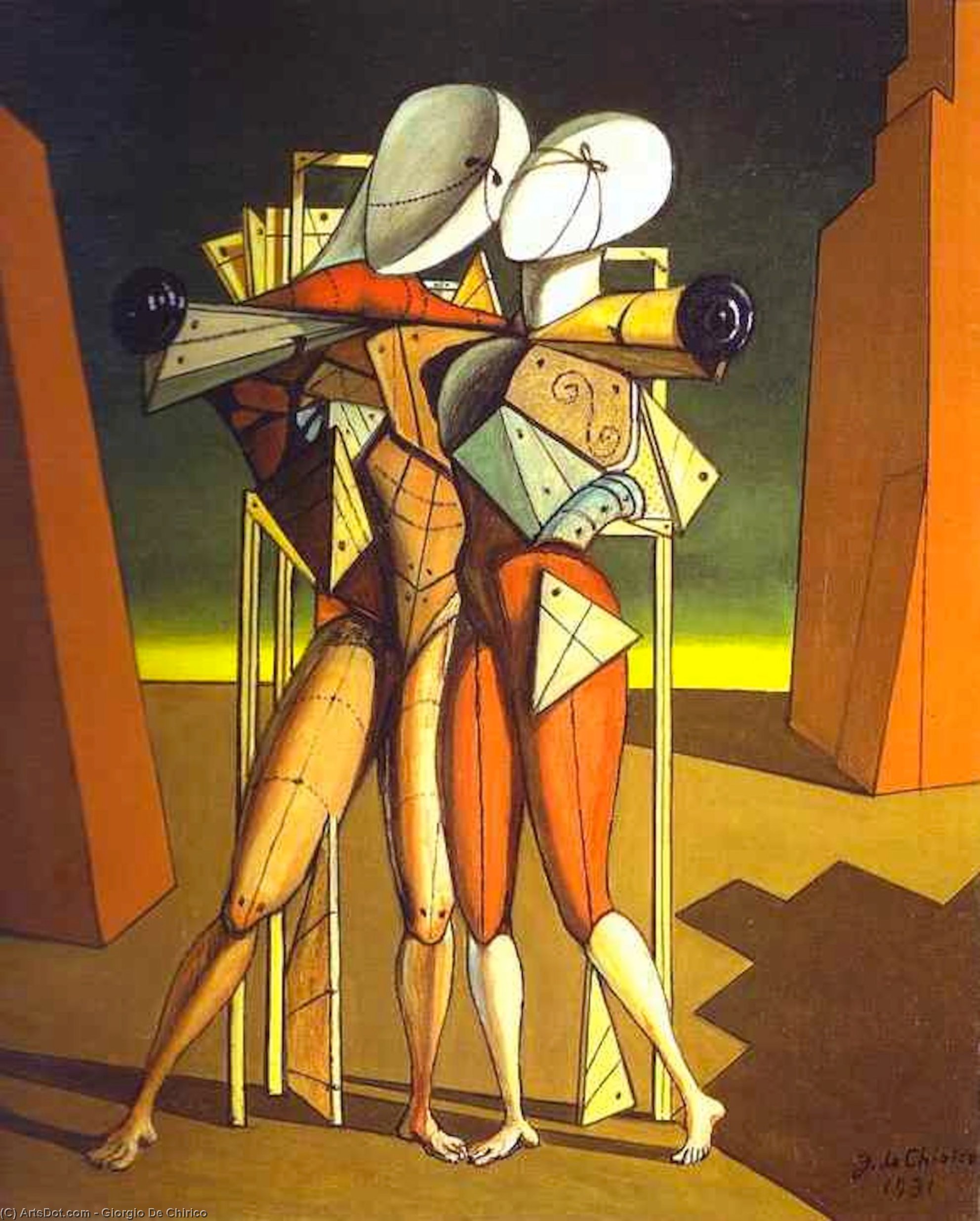

Le sue piazze sono estranianti, i suoi manichini senza volto richiamano l’impossibilità di vedere, udire e parlare e sembrano automi privi di emozioni, i cavalli privi di occhi, considerati un organo che distrae, ciechi come Omero, corrono lungo la spiaggia in un ambiente lunare e onirico. E’ il gioco della metafisica, il così è se vi pare, è lasciare l’osservatore muto e sbigottito in cerca di risposte, in un crescendo di dilemmi insolubili. Nell’arte di De Chirico si riesce a vedere il silenzio.

De Chirico’s world is made up of elements that we recognize as part of our cultural heritage, united together in a new way, with a different grammar that creates the enigma. Even though he uses real objects (statues, mannequins, squares, rulers, columns, famous monuments), De Chirico disassembles them through a thorough analysis, drawing us into his dreamlike and visionary world. His intimate narrative unfolds through shapes, perspectives, and colors borrowed from classical painting.

His squares are alienating, his faceless mannequins evoke the impossibility of seeing, hearing, and speaking; they seem like emotionless automatons. Horses without eyes, considered a distracting organ, run along the beach in a lunar and dreamy setting, blind like Homer. It’s the game of metaphysics, the “it is so if you think so,” leaving the observer speechless and amazed, searching for answers in an increasing crescendo of insoluble dilemmas. In De Chirico’s art, you can perceive silence.

De Chirico si muove in un’epoca dove trionfa il pensiero filosofico positivista, quello delle certezze, delle scoperte, della scienza; egli scompiglia tutto, affermando di adorare i dubbi e gli enigmi.

“Deduco, si può concludere che ogni cosa abbia due aspetti: uno corrente, quello che vediamo quasi sempre e che vedono gli uomini in generale, l’altro lo spetrale o metafisico che non possono vedere che rari individui in momenti di chiaroveggenza e di astrazione metafisica, così come certi corpi occultati da materia impenetrabile ai raggi solari non possono apparire che sotto la potenza di luci artificiali quali sarebbero i raggi x.“ Giorgio De Chirico

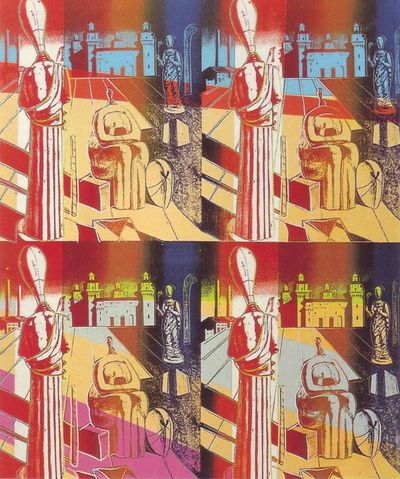

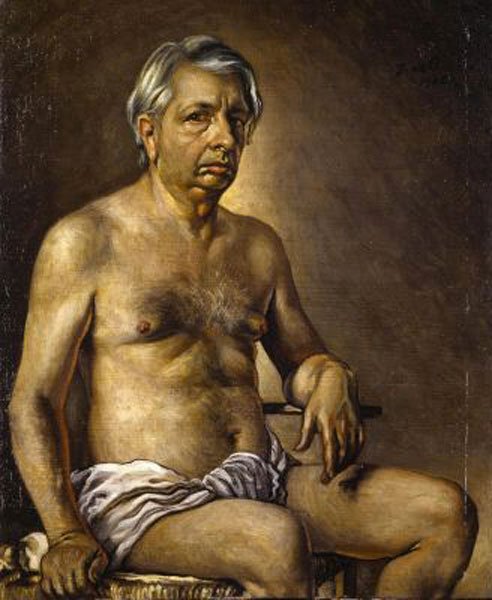

La stessa serialità dei dipinti è spiazzante, De Chirico dipinge senza soluzione di continuità le Piazze d’Italia, ognuna con una piccola variante, le Muse inquietanti, gli archeologi, i cavalli, i manichini sono temi replicati, passando dalla Metafisica del primo novecento alla Neometafisica degli anni ’50, ’60 e ’70 dove i soggetti hanno acquisito una luce chiara perdendo l’aspetto angosciante dell’enigma; una serialità che colpisce, quasi come una folgorazione, Andy Warhol che fotografa due sue opere e le riproduce con la sua consueta serialità serigrafica. In mostra, nell’ultima sala, sono presenti tre dipinti delle muse inquietanti contrapposti ad una grande serigrafia di Warhol delle stesse.

De Chirico moves within an era dominated by positivist philosophical thought, one of certainties, discoveries, and science; he disrupts everything, asserting his adoration for doubts and enigmas.

“I deduce that everything has two aspects: one current, which we almost always see and which is seen by people in general, the other spectral or metaphysical, which can only be seen by rare individuals in moments of clairvoyance and metaphysical abstraction, just as certain bodies hidden by impenetrable matter to sunlight can only appear under the power of artificial lights such as X-rays.” – Giorgio De Chirico

The same seriality of the paintings is unsettling; De Chirico paints the Piazze d’Italia continuously, each with a slight variation. The haunting Muses, the archaeologists, the horses, and the mannequins are replicated themes, transitioning from the Metaphysical of the early 20th century to the Neometaphysical of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, where the subjects have gained a clear light, losing the distressing aspect of the enigma. It’s a seriality that strikes, almost like a revelation, reminiscent of Andy Warhol, who photographs two of his own works and reproduces them with his customary serigraphic seriality. In the exhibition, in the final room, three paintings of the haunting Muses are juxtaposed with a large Warhol serigraphy of the same.

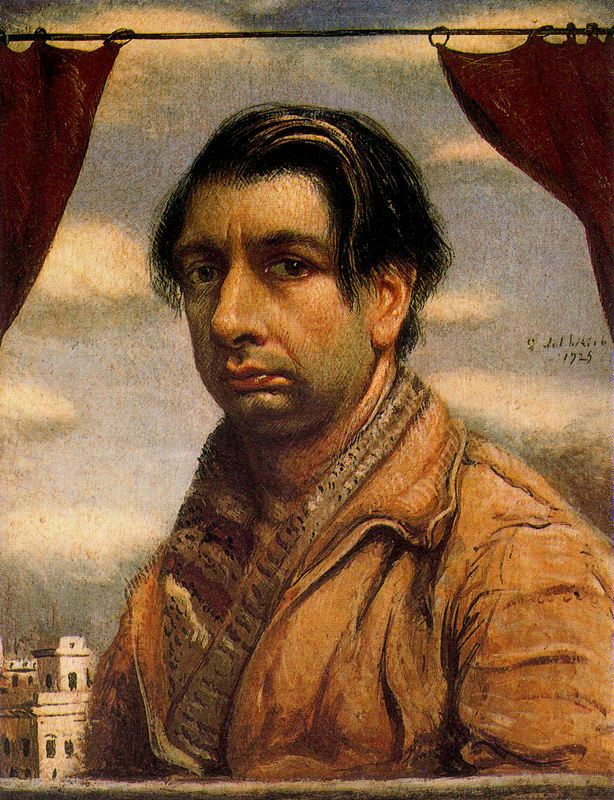

Una personalità molto discussa, a volte amata altre detestata quella di De Chirico, uno spirito ironico che non si prende mai troppo sul serio. Il mito greco che oscilla fra serietà e ironia. Nelle sue repliche egli stesso diventa, ispirandosi allo Zarathustra Nietzscheriano, il “ritornante” .

L’ultima mostra dedicata a De Chirico, sempre a Palazzo Reale, venne fatta nel 1970 e Dino Buzzati la recensì con queste parole: “I più recenti quadri, esposti nell’ultima sala non sono pedisseque ripetizioni di vecchi quadri metafisici comparsi negli anni scorsi. Si tratta di invenzioni genuine, inedite.”

A highly debated personality, sometimes loved and at other times despised, that of De Chirico, a spirit of irony that never takes itself too seriously. The Greek myth oscillating between seriousness and irony. In his repetitions, he himself becomes, inspired by Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, the “returning” figure.

The last exhibition dedicated to De Chirico, also at Palazzo Reale, took place in 1970 and was reviewed by Dino Buzzati with these words: “The most recent paintings, displayed in the final room, are not mere repetitive replicas of old metaphysical paintings that appeared in previous years. They are genuine, unpublished inventions.”

(*) https://giusybaffi.com/carlo-carra-a-palazzo-reale-di-milano/

©Giusy Baffi 2019 (parzialmente pubblicato su ArteVitae.it. 28 ottobre 2019)

© Le foto sono state reperite da libri e cataloghi d’asta o in rete e possono essere soggette a copyright. L’uso delle immagini e dei video sono esclusivamente a scopo esplicativo. L’intento di questo blog è solo didattico e informativo. Qualora la pubblicazione delle immagini violasse eventuali diritti d’autore si prega di volerlo comunicare via email a info@giusybaffi.com e saranno prontamente rimosse oppure citato il copyright ©.

© Il presente sito https://www.giusybaffi.com/ non è a scopo di lucro e qualsiasi sfruttamento, riproduzione, duplicazione, copiatura o distribuzione dei Contenuti del Sito per fini commerciali è vietata.

©The photos have been sourced from the internet and may be subject to copyright. The use of the images is solely for explanatory purposes. The intention of this blog is purely educational and informative. If the publication of the images were to infringe upon any copyright, please notify us via email at info@giusybaffi.com, and they will be promptly removed or the copyright will be cited as ©.

© The current website https://www.giusybaffi.com/ is not for profit, and any exploitation, reproduction, duplication, copying, or distribution of the Site’s Content for commercial purposes is prohibited.