PREZIOSITA’ GUERRIERE – I gioielli dei samurai – PRECIOUS WARRIORS – The Jewels of the Samurai

Gli oggetti preziosi dei samurai: l’importanza dell’eleganza e della raffinatezza nella ricerca estrema del dettaglio prezioso, nel contesto della gestualità rituale.

In Giappone, fino al 1868, vigeva una politica fondata su un sistema centrale rappresentato dalla figura dell’Imperatore e una gestione feudale del territorio basato sul potere conferito dall’Imperatore stesso agli shogun o reggenti.

I samurai erano guerrieri attivi che combattevano per proteggere il loro shogun mettendo a repentaglio la loro stessa vita.

The Precious Objects of the Samurai: The Importance of Elegance and Refinement in the Quest for Exquisite Detail, within the Context of Ritual Gestures.

In Japan, until 1868, a policy based on a central system represented by the Emperor and a feudal management of the territory prevailed, founded on the power granted by the Emperor himself to the shoguns or regents.

Samurai were active warriors who fought to protect their shogun, risking their own lives in the process.

Essi appartenevano alla casta nobile e colta, occupavano una posizione importante all’interno della società e tutti coloro che si trovavano sotto di loro erano tenuti ad obbedirli e a rispettarli.

Nell’eseguire il proprio dovere seguivano una filosofia nota come “la via del samurai” o “bushido” codice di condotta basato sul concetto d’onore affiancato dalla fedeltà al proprio signore.

Scrive Yamamoto Tsunetomo, (1659 – 1721) militare e filosofo nel suo Hagakure, il Codice dei Samurai: “Il samurai dovrebbe essere un uomo di gusto eccellente ovvero estremamente affascinante”

They belonged to the noble and cultured caste, holding a significant position within society, and all those beneath them were required to obey and respect them.

In carrying out their duty, they followed a philosophy known as ‘the way of the samurai’ or ‘bushido’ – a code of conduct based on the concept of honor, accompanied by loyalty to their lord.

Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659 – 1721), a military officer and philosopher, writes in his “Hagakure,” the Code of the Samurai: “A samurai should be a man of exquisite taste, in other words, extremely fascinating.”

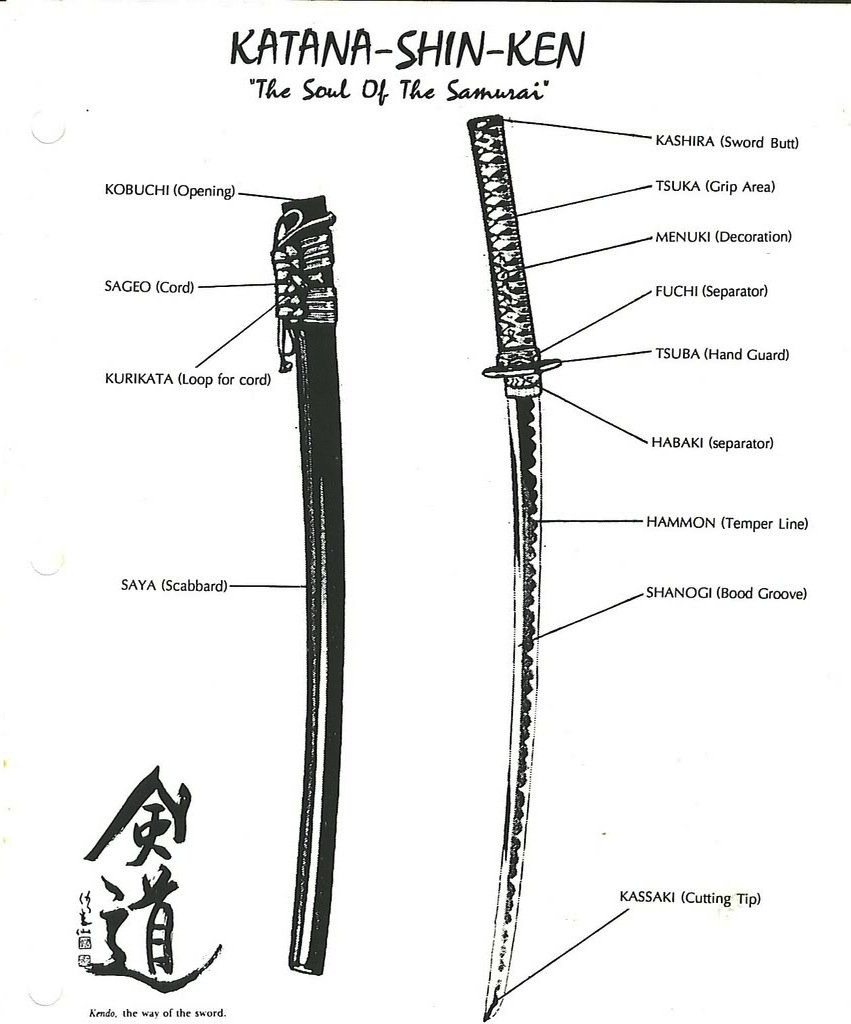

LA SPADA

Il detto secondo cui “la spada è l’anima del samurai” riassume perfettamente il rapporto che legava un guerriero alla sua arma.

Il samurai veniva iniziato allo studio dell’uso della spada dall’età di cinque anni, in un continuo e costante perfezionamento.

Con un fortissimo valore simbolico, la spada era il distintivo della classe sociale d’appartenenza, uno strumento da guerra, un’opera d’arte.

Rinunciare alla propria arma era come rinunciare alla vita.

Un samurai non possedeva altra ricchezza che la sua spada portata in coppia: il katana, spada lunga ed affilatissima usata per l’esterno e il Wakizashi spada corta, usata anche come coltello per il suicidio rituale e che veniva sempre indossata. La coppia delle spade è chiamato daisho.

Le spade erano realizzate con acciaio della migliore qualità. La spada restava immersa nel calore della fornace per diversi giorni per poi essere battuta e ribattuta in modo da risultare affilata al punto di poter tagliare la testa di un uomo con un colpo solo.

Ogni spada aveva un cuore in metallo morbido avvolto da un metallo più duro i cui bordi venivano temprati fino a raggiungere la massima durezza; la lama quindi era tagliente come quella di un rasoio mentre il corpo della spada garantiva la massima resistenza e affidabilità.

La fabbricazione della spada era considerata un’operazione sacra, forgiare queste lame era un’arte, le spade migliori erano firmate e addirittura battezzate con un nome.

THE SWORD

The saying “the sword is the soul of the samurai” perfectly encapsulates the relationship that bound a warrior to their weapon.

A samurai would begin learning the use of the sword from the age of five, in a continuous and relentless pursuit of mastery.

With incredibly strong symbolic value, the sword was the emblem of their social class, a tool of war, a work of art.

To give up one’s weapon was akin to giving up one’s life.

A samurai possessed no other wealth than their paired swords: the katana, a long and extremely sharp sword used for outdoor combat, and the wakizashi, a shorter sword also used as a knife for ritual suicide, which was always worn. The pair of swords was called daisho.

These swords were crafted from the highest quality steel. The sword was left immersed in the forge’s heat for several days, then repeatedly beaten and folded, resulting in an edge so sharp that it could sever a man’s head with a single strike.

Each sword had a soft metal core enveloped by a harder metal, with the edges tempered to achieve the utmost hardness; the blade was thus as sharp as a razor, while the body of the sword guaranteed maximum strength and reliability.

The crafting of the sword was considered a sacred operation; forging these blades was an art. The finest swords were signed and sometimes even christened with a name.

Ma erano le parti accessorie alla lama le vere “vanità” dei samurai.

Mentre per la guerra queste dovevano risultare essenziali e utili, in tempo di pace riflettevano la natura e l’ostentazione dei loro proprietari.

Le lame potevano “vestire” montature da guerra, da riposo, da cerimonia, è facile riscontrare montature di epoca posteriore alla lama, proprio perché suscettibili alle mode.

Il fodero (saya) ha il compito importantissimo di proteggere la lama non solo dagli urti ma anche dall’aria e dall’umidità. A tale scopo esso viene laccato facendo entrare nella costruzione dei “fornimenti” una categoria di artigiani famosi ed apprezzati: i laccatori.

La lacca che viene stesa sul legno del saya è la stessa che viene usata ancora oggi. Si tratta della linfa di una pianta (rhus vernicifera) e viene applicata a strati successivi, da un minimo di 75 strati fino ad arrivare a oltre 130.

La durata dell’essiccazione, da cui dipende la penetrazione nel legno, va dai due ai quattro anni.

Ciò basta a far capire quale importanza venga data alla protezione della lama.

Sia il fodero che l’impugnatura erano in legno di magnolia, sull’impugnatura veniva avvolta, in diversi stili, una fettuccia che aveva la doppia funzione di miglior presa e di assorbimento del sudore.

But it was the accessory parts of the sword that were the true “vanities” of the samurai.

While these accessories needed to be essential and functional for warfare, in times of peace, they reflected the nature and ostentation of their owners.

The blades could be “dressed” in various mounts for battle, resting, or ceremonial purposes. It’s common to find mounts from later periods than the blade itself, as they were susceptible to trends and fashions.

The scabbard (saya) had the crucial role of protecting the blade not only from impacts but also from air and moisture. To achieve this, lacquer was applied to the construction of the fittings, involving a category of skilled and esteemed artisans: the lacquerers.

The lacquer applied to the wood of the saya is the same used today. It’s made from the sap of a plant (rhus vernicifera) and is layered in multiple coats, ranging from a minimum of 75 layers to over 130 layers.

The drying process, which determines how deeply the lacquer penetrates the wood, takes between two to four years.

This underscores the importance placed on protecting the blade.

Both the scabbard and the hilt were made from magnolia wood. The hilt was wrapped in various styles with a cord that had a dual function of providing a better grip and absorbing sweat.

Altra parte importante della spada è la guardia (tsuba), quell’elemento di metallo che separa la lama dall’impugnatura, un disco in ferro.

Di forma circolare o quadrata era inizialmente forgiato dagli stessi armieri e forgiatori di spade, ma durante tutto il periodo Edo (1615-1867) divenne opera degli artigiani e degli orafi che si sbizzarrirono nel creare nuove leghe sempre più preziose con la superficie incisa e riccamente ornata da racconti mitologici, religiosi, rappresentazioni simboliche e naturalistiche, dei veri e propri capolavori di arte applicata.

Another important part of the sword is the guard (tsuba), the metal element that separates the blade from the hilt, a disc made of iron.

Initially, these circular or square shapes were forged by the same swordsmiths and blade forgers, but during the entire Edo period (1615-1867), they became the work of artisans and goldsmiths who indulged in creating new, increasingly precious alloys. These guards had surfaces intricately engraved and richly decorated with mythological, religious, symbolic, and naturalistic depictions. They evolved into true masterpieces of applied art.

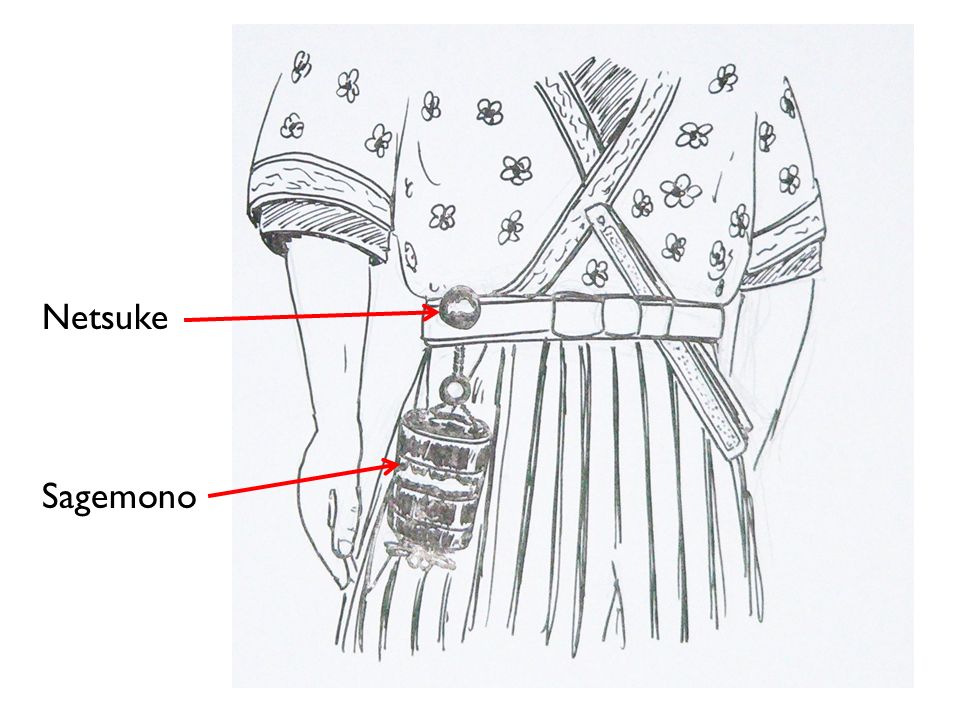

GLI OGGETTI SOSPESI – I SAGEMONO

Giada, corallo, ambra, avorio, osso, corno, lacca, porcellana e poi ebano, magnolia, camelia, bambù, canfora, bosso, cipresso, metallo: sono questi i materiali scolpiti o incisi di cui sono fatti i netzuke, bottoni che fuoriuscivano dall’obi, fascia usata come cintura del kimono, ai quali erano appesi, per mezzo di un cordoncino di seta una serie di piccoli accessori che dovevano supplire alla mancanza di tasche dei kimono.

HANGING OBJECTS – SAGEMONO

Jade, coral, amber, ivory, bone, horn, lacquer, porcelain, and then ebony, magnolia, camellia, bamboo, camphor, boxwood, cypress, metal: these are the carved or engraved materials used for creating netsuke, small buttons that protruded from the obi, the sash worn as a belt for the kimono. Hanging from them, by means of a silk cord, a series of small accessories were attached to compensate for the absence of pockets in kimonos.

Questi oggetti sospesi sono chiamati sagemono o koshisage avevano una funzione pratica essendo i contenitori per tutti gli accessori utili alla vita quotidiana: portamonete, porta-medicine, custodie per pipe e tabacco, porta-sigilli, porta-profumo, completo da scrittura.

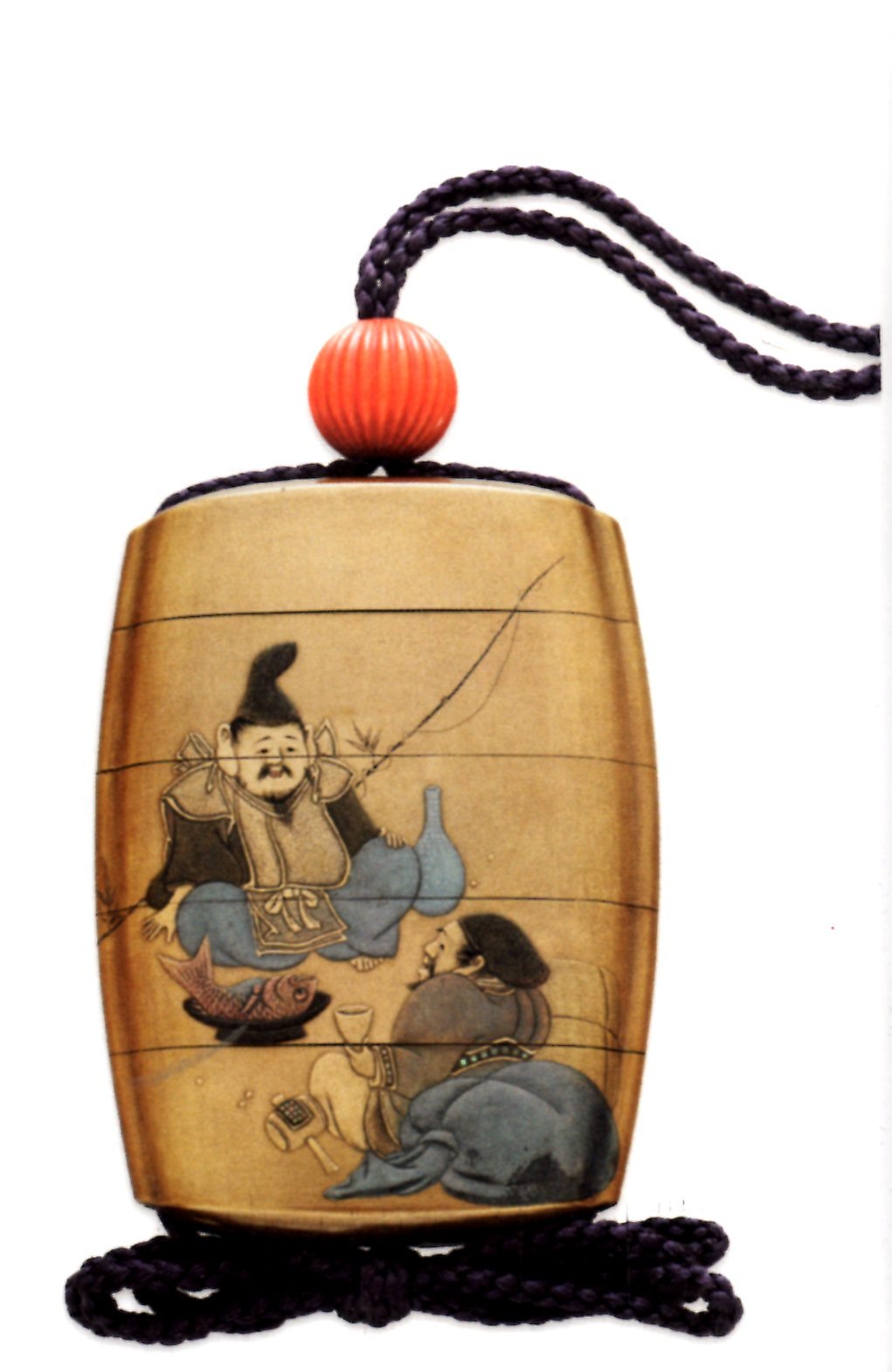

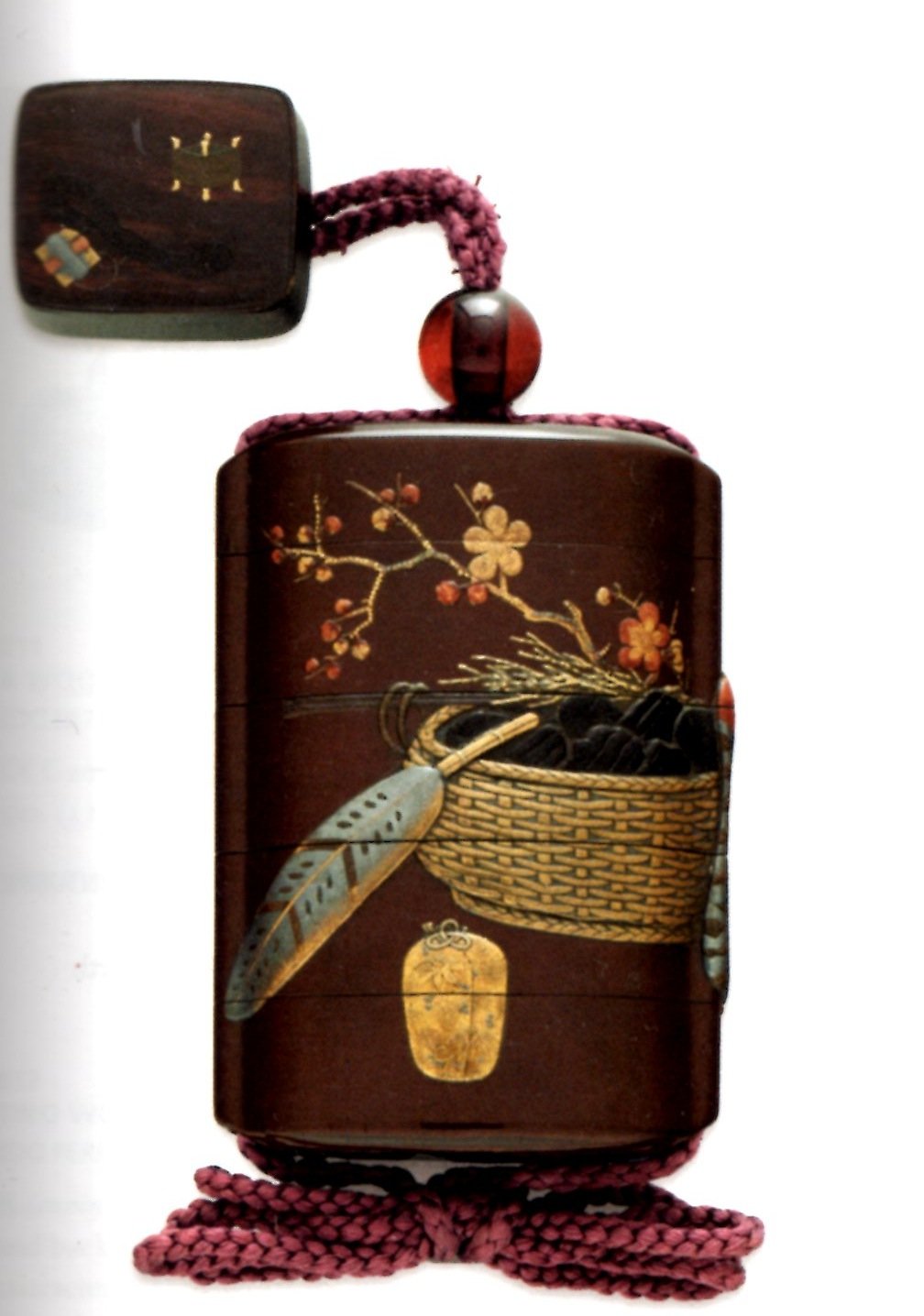

Gli inro sono delle piccole scatole da uno a sette comparti sovrapposti e tenuti insieme da una piccola corda, erano portati sul lato destro del corpo. Concepiti inizialmente come porta-medicine, divennero in seguito dei veri e propri status-symbols da esibire. Realizzati prevalentemente in lacca o in avorio la loro superficie si prestava a stupefacenti esecuzioni artistiche.

These suspended objects are called “sagemono” or “koshisage.” They served a practical function, as they were containers for various useful everyday items: coin purses, medicine cases, pipe and tobacco pouches, seal holders, perfume containers, and writing sets.

The “inro” are small boxes with one to seven stacked compartments, held together by a cord and worn on the right side of the body. Initially conceived as medicine cases, they later became true status symbols to display. Primarily crafted from lacquer or ivory, their surfaces lent themselves to astonishing artistic executions.

Inro firmato Yoshigawa. Periodo Edo - metà XIX sec. ©Buddha Museum - Collezione privata

Inro firmato Yoshigawa. Periodo Edo - metà XIX sec. ©Buddha Museum - Collezione privata

Inro firmato Yoshigawa. Periodo Edo - metà XIX sec. ©Buddha Museum - Collezione privata

Inro firmato Yoshigawa. Periodo Edo - metà XIX sec. ©Buddha Museum - Collezione privata

Busta e tubo per il tabacco con Netsuke di perla d’acqua dolce. XVIII secolo – ©Metropolitan Museum – New York

Inro laccato e dipinto firmato Zeshin, XIX sec. © Christie’s New York

Inro avorio di elefante periodo Meiji (1868-1912)

Inro laccato e dipinto con netzuke en suite, XIX sec. © Christie’s New York

Gli stessi netzuke avevano spesso una doppia funzione, sia pratica che decorativa, troviamo netzuke in avorio che fungevano da sigillo utilizzato per convalidare atti legali, autentiche per pitture, stampe e altri oggetti di valore artistico, altri scolpiti con i segni dello zodiaco, animali, figure mitologiche, figure religiose legate allo Shintoismo, al Taoismo e al Buddismo, altre ancora legate ai miti e alle leggende del Sol Levante.

Erano considerati anche simbolo di buon auspicio e la loro forma era prevalentemente arrotondata, evitando sporgenze o spigoli perché dovevano rispondere a particolari sensazioni al tatto e nello stesso tempo non impigliarsi nei kimono.

Realizzati in una varietà di forme e nei materiali più disparati tra cui, oltre che in avorio e in legno, anche in porcellana, in lacca e in metallo.

Sia i netzuke che i sagemono si prestarono ampiamente, dal XVIII secolo in poi, alla fantasia, estrosità e abilità dei carvers, la categoria di intagliatori ed incisori specializzati nella lavorazione dell’avorio, del legno, del corallo.

The same netsuke often served a dual function, both practical and decorative. There are ivory netsuke that acted as seals used to validate legal documents or authenticate paintings, prints, and other valuable artistic items. Others were carved with zodiac signs, animals, mythological figures, religious figures associated with Shintoism, Taoism, and Buddhism, as well as myths and legends from the Land of the Rising Sun.

They were also considered symbols of good luck, and their shape was predominantly rounded, avoiding protrusions or sharp edges to cater to specific tactile sensations while not getting caught in kimonos.

Crafted in a variety of forms and diverse materials, including not only ivory and wood but also porcelain, lacquer, and metal.

Both netsuke and sagemono were widely embraced by carvers, especially from the 18th century onward. These skilled artisans specialized in working with materials like ivory, wood, and coral, showcasing their creativity, inventiveness, and craftsmanship.

Ryusa netzuke scolpito su ambedue le facce - XIX secolo

netzuke in lacca rossa – Sec. XVIII – © Metropolitan Museum – New York

Netsuke d'avorio di bue - Scuola di Kyoto, XVIII secolo © Giuseppe Piva antiquario

netzuke in avorio attribuito al carver Ryūsa secolo XVIII – ©Metropolitan Museum – New York

Netzuke in avorio firmato Masayuki e Kao - periodo Edo XIX secolo.

gruppo di netzuke fine ‘800 © Christie’s Londra

L’EPILOGO

L’era dei samurai e la fine del dominio delle caste guerriere giunge al termine del periodo Edo, quando il vecchio sistema feudale con il suo Shogun è sostituito dal nuovo governo centralizzato dell’Imperatore Meiji che inizia un profondo programma di riforme modificando la struttura economica, politica e sociale del Paese.

I samurai perdono prestigio sociale, si trasformano in burocrati e la loro spada viene usata, ancora per poco, solo per scopi cerimoniali fino a quando, nel 1877 anno in cui tentano di rovesciare il nuovo governo, non sono più autorizzati a portare la spada in pubblico.

THE EPILOGUE

The era of the samurai and the end of the dominion of warrior castes comes to a close at the end of the Edo period, when the old feudal system with its Shogun is replaced by the new centralized government of Emperor Meiji. This marks the beginning of a profound program of reforms that alter the economic, political, and social structure of the country.

Samurai lose their social prestige, transforming into bureaucrats, and their swords are used, albeit briefly, only for ceremonial purposes. This continues until 1877 when they attempt to overthrow the new government, leading to the prohibition of openly carrying swords.

Bibliografia:

Thurnbull Steven – Samurai, the Story of Japan’s Noble Warriors – Collins & Brown 2004

Lanfranchi – Il netzuke un’arte giapponese– Secomandi 1962

www.japanese-sukashi-tsuba.com

©Giusy Baffi 2020 – (Pubblicato su Cose Belle Antiche e Moderne 2011 – ArteVitae.it 13 settembre 2018)

© Le foto sono state reperite da libri e cataloghi d’asta o in rete e possono essere soggette a copyright. L’uso delle immagini e dei video sono esclusivamente a scopo esplicativo. L’intento di questo blog è solo didattico e informativo. Qualora la pubblicazione delle immagini violasse eventuali diritti d’autore si prega di volerlo comunicare via email a info@giusybaffi.com e saranno prontamente rimosse oppure citato il copyright ©.

© Il presente sito https://www.giusybaffi.com/ non è a scopo di lucro e qualsiasi sfruttamento, riproduzione, duplicazione, copiatura o distribuzione dei Contenuti del Sito per fini commerciali è vietata.

© The photos have been sourced from books, auction catalogs, or online and may be subject to copyright. The use of images and videos is solely for explanatory purposes. The intent of this blog is purely educational and informational. If the publication of images were to violate any copyright, please communicate this via email to info@giusybaffi.com, and they will be promptly removed or the copyright © will be cited.

© The present website https://www.giusybaffi.com/ is not for profit, and any exploitation, reproduction, duplication, copying, or distribution of the Site’s Content for commercial purposes is prohibited.