I MOBILI IN CRISTALLO, una fragile passione del ‘700 e ‘800 – CRYSTAL FURNITURE, a fragile passion of the 18th and 19th centuries

Tra le fine del 1700 e il 1800 la Russia, L’Europa e l’India impazzirono per la moda di arredi completamente in cristallo, di altissima committenza, che sono ora esposti nei più grandi Musei o al sicuro in collezioni private.

Between the late 1700s and the 1800s, Russia, Europe, and India went crazy for the fashion of furniture entirely made of crystal, commissioned at the highest level, which is now exhibited in the largest museums or safely stored in private collections.

LA RUSSIA

Pare che questa moda sia partita dalla Russia quando, verso il 1780, l’imperatrice Caterina II ordinò dei tavoli in cristallo alle Manifatture Imperiali del Vetro e del Cristallo di San Pietroburgo per il Palazzo di Tsarskoye Selo, la sua residenza appena fuori San Pietroburgo.

Nello stesso periodo l’architetto scozzese Charles Cameron (1740-1812) progettò per l’Imperatrice di Russia un’intera stanza con soffitto, pareti, colonne e porte in cristallo; i mobili erano realizzati con lastre di cristallo blu, mentre il soffitto era in vetro eglomizzato decorato con figure in oro. Purtroppo questa camera spettacolare venne irrimediabilmente distrutta durante la seconda guerra mondiale.

La Russia, contrariamente all’Europa e all’India, è sempre stata particolarmente attratta dai cristalli colorati e questo gusto trova la sua espressione non solo nel piccolo tavolino rettangolare con gambe in vetro blu scuro e il piano in opaline bianca, eseguito su disegno di Charles Cameron dalla Manifattura Imperiale nel 1780, ma anche nel tavolino ottagonale il cui piano in vetro blu scuro è sostenuto da una gamba centrale conica in vetro soffiato color ambra poggiante su una base quadrata in vetro color ambra scura e piedi in metallo dorato.

IN RUSSIA

It seems that this trend started in Russia when, around 1780, Empress Catherine II ordered crystal tables from the Imperial Glass and Crystal Manufactories of St. Petersburg for the Tsarskoye Selo Palace, her residence just outside St. Petersburg.

During the same period, the Scottish architect Charles Cameron (1740-1812) designed an entire room with a ceiling, walls, columns, and doors made of crystal for the Empress of Russia. The furniture was made of blue crystal slabs, while the ceiling was gilded glass decorated with figures in gold. Unfortunately, this spectacular room was irreparably destroyed during the Second World War.

Contrary to Europe and India, Russia has always been particularly attracted to colored crystals. This taste is expressed not only in the small rectangular table with dark blue glass legs and a white opaline top, executed according to Charles Cameron’s design by the Imperial Manufacture in 1780, but also in the octagonal table with a dark blue glass top supported by a central conical leg made of blown amber glass resting on a square base in dark amber glass and feet in gilded metal.

LA FRANCIA

Nello stesso periodo fiorirono in Francia le manifatture di cristalli di Saint Louis, di Baccarat e di Creusot.

Gli oggetti in cristallo venivano spesso affidati a dei “montatori” per essere montati su bronzo, oro o argento; tra questi abilissimi professionisti figura Madame Marie-Jeanne Désarnaud-Charpentier, che fu la prima persona ad avere sia la fantasia che l’audacia di eseguire dei mobili interamente in cristallo. I cristalli le venivano forniti dalla manifattura Vonèche in Belgio e, dopo il 1816, dalla manifattura Baccarat.

Il suo laboratorio “A l’escalier de cristal”, fondato nel 1802, si trovava all’interno del parigino Palais Royal ed era specializzato in oggetti e mobili in cristallo montati in bronzo dorato.

IN FRANCE

In the same period, crystal manufactories thrived in France, including Saint Louis, Baccarat, and Creusot.

Crystal objects were often entrusted to “mounters” to be mounted on bronze, gold, or silver. Among these skilled professionals was Madame Marie-Jeanne Désarnaud-Charpentier, who was the first person to have both the imagination and audacity to create furniture entirely made of crystal. The crystals were supplied to her by the Vonèche manufactory in Belgium and, after 1816, by the Baccarat manufactory.

Her workshop, “A l’escalier de cristal,” founded in 1802, was located within the Palais Royal in Paris and specialized in crystal objects and furniture mounted in gilded bronze.

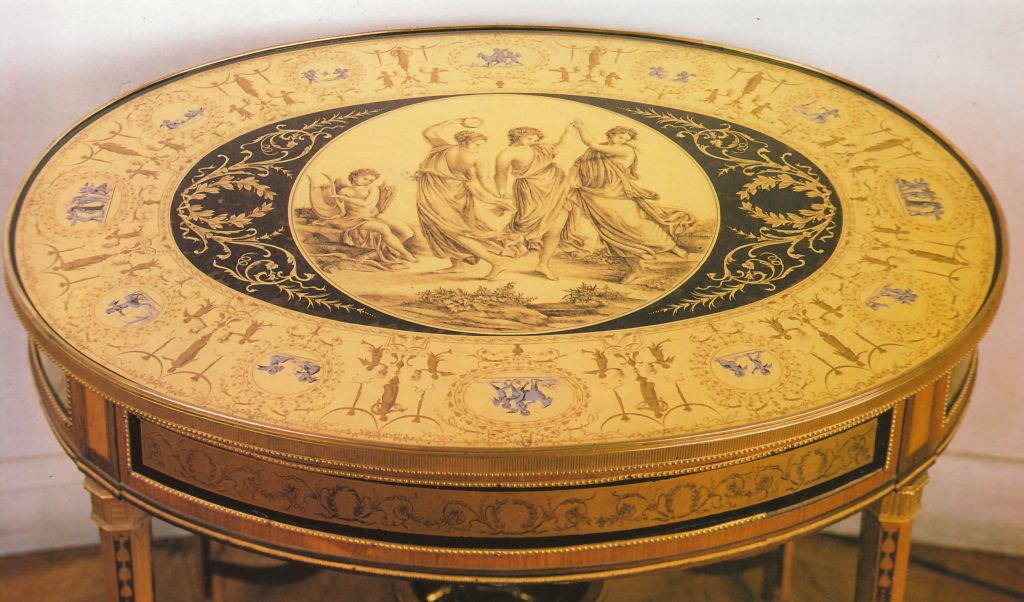

A questa produzione appartengono la toilette e la poltrona, disegnate da Nicolas-Henry Jacob, ancora in pieno stile napoleonico: il tavolo da toeletta, sormontato da uno specchio basculante, ha il piano in vetro eglomizzato a fondo blu, nella fascia sottopiano è presente un cassetto che contiene un meccanismo musicale che suona, come precisano le cronache dell’epoca, “per la durata di un’ ora: suona cioè per lo spazio di tempo in cui una signora carina possa decentemente passare davanti ad uno specchio, in presenza di se stessa.” Il mobile poggia su gambe a forma di cornucopie e su due colonnine a balaustro.

Lo specchio basculante è sostenuto da due colonne accanto alle quali spiccano le figurine in bronzo dorato di Flora e Zefiro.

This production includes the dressing table and armchair, designed by Nicolas-Henry Jacob, still in the full Napoleon style. The dressing table, topped with a tilting mirror, has a blue background gilded glass top. In the under-table band, there is a drawer containing a musical mechanism that plays, as the chronicles of the time specify, “for the duration of an hour: it plays for the amount of time during which a charming lady can decently pass in front of a mirror, in the presence of herself.” The piece stands on legs shaped like cornucopias and two baluster columns.

The tilting mirror is supported by two columns, next to which stand the gilded bronze figurines of Flora and Zephyr.

Toilette disegnata da Nicolas-Henry Jacob,con piano eglomizzato e poltrona appartenuta alla duchesse De Berry, produzione “A l’escalier de cristal” 1819 circa – Museo del Louvre ©

Toilette disegnata da Nicolas-Henry Jacob, con piano eglomizzato e poltrona appartenuta alla duchesse De Berry, produzione “A l’escalier de cristal” 1819 circa – Museo del Louvre ©

L’INGHILTERRA

Pezzi del genere hanno sicuramente ispirato il britannico Thomas Osler e suo figlio, la loro manifattura F.& C. Osler ltd., fondata a Birmingham nel 1807, si era specializzata nella produzione di mobili in cristallo. Osler fu probabilmente il primo produttore europeo di arredi in cristallo che intuì il grandissimo potenziale del mercato indiano per questi oggetti spettacolari.

IN ENGLAND

Pieces of this kind certainly inspired the British Thomas Osler and his son. Their manufacturing company, F. & C. Osler Ltd., founded in Birmingham in 1807, specialized in the production of crystal furniture. Osler was likely the first European manufacturer of crystal furniture to recognize the enormous potential of the Indian market for these spectacular objects.

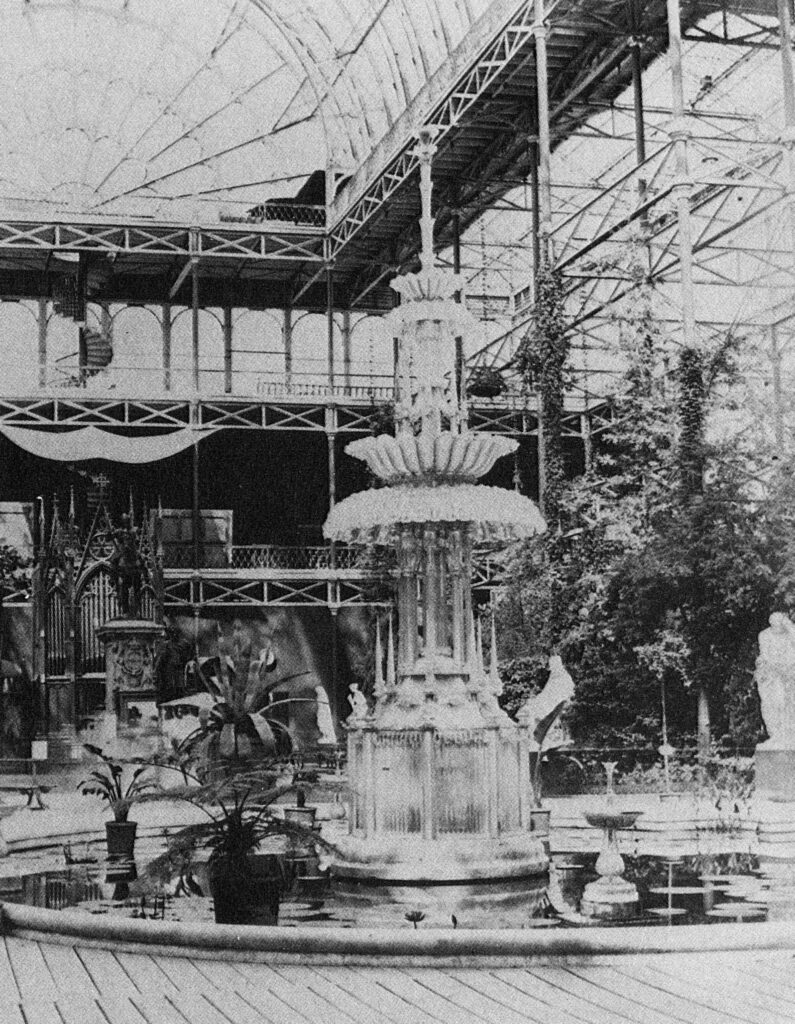

Nell’Esposizione Internazionale del 1851 tenutasi nel Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, a Londra, Osler presentò una fontana completamente in cristallo alta più di 8 metri e contenente oltre 4 tonnellate di cristalli.

Dopo questa esposizione, che lo rese famoso a livello mondiale, Osler iniziò a fornire diversi palazzi di maragià indiani con interi arredi in cristallo.

After this exhibition, which made him famous worldwide, Osler began to supply various Indian maharajas’ palaces with entire crystal furnishings.

L’INDIA

Per il palazzo di Jai Vilas Palace del maragià di Gwalior egli fornì, oltre gli enormi lampadari da 248 luci (si racconta che il maragià, per essere sicuro che il soffitto avrebbe sopportato un peso simile, fece salire alcuni elefanti sul tetto), anche un gran numero di tavoli, sedie, armadi, stipi, chaises longues.

IN INDIA

For the Jai Vilas Palace of the Maharaja of Gwalior, Osler supplied not only enormous chandeliers with 248 lights (legend has it that the Maharaja, to ensure that the ceiling could bear such weight, had some elephants brought up to the roof) but also a large number of tables, chairs, wardrobes, cabinets, and chaises longues.

Nel 1890 anche Baccarat, Compagnie des Verreries et Cristalleries, la famosa manifattura parigina di cristalli fondata nel 1764, entrò nel mercato indiano di Bombay producendo mobili; si racconta che in India Baccarat trasportasse con gli elefanti i suoi delicatissimi mobili in cristallo.

In 1890, even Baccarat, the famous Parisian crystal manufacturer founded in 1764 as Compagnie des Verreries et Cristalleries, entered the Indian market in Bombay by producing furniture. It is said that in India, Baccarat transported its delicate crystal furniture using elephants.

Certamente l’idea che un mobile possa brillare come un diamante, mandare bagliori come una preziosa gemma colorata senza perdere la sua funzione primaria di utilizzo sbalordisce, e non poco, chi si imbatte nei mobili di cristallo del XIX secolo.

⇒ Vetro eglomizzato è un termine per descrivere l’applicazione di sottilissime foglie d’oro e d’argento applicate insieme a dei colori sul retro di una lastra di vetro. Il disegno si ottiene incidendo la foglia di metallo, applicata e opportunamente trattata, con una punta d’agata. La gamma dei colori era: oro, argento, nero, turchese, bianco e celeste coniugati in varie combinazioni e i disegni erano molto spesso di ispirazione classica. Questa tecnica dalle origini antichissime, è stata utilizzata in epoca pre-romana e poi nel Medioevo e nel Rinascimento.

⇒Il termine eglomizzato viene coniato nel 1825 e deriva da Jean Baptiste Glomy (1711-1786), encadreur di Luigi XVI che utilizzò questa tecnica per gli specchi e le cornici dei quadri di proprietà di Maria Antonietta.

“Verre églomisé is a term used to describe the application of extremely thin leaves of gold and silver, along with colors, on the back of a glass sheet. The design is achieved by engraving the metal leaf, which is applied and properly treated with an agate-tipped tool. The color range includes gold, silver, black, turquoise, white, and sky blue, combined in various combinations, and the designs often draw inspiration from classical motifs. This technique, with ancient origins, was used in pre-Roman times and later during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

The term “eglomisé” was coined in 1825 and derives from Jean Baptiste Glomy (1711-1786), a framer (encadreur) of Louis XVI, who employed this technique for mirrors and picture frames owned by Marie Antoinette.

©Giusy Baffi 2020 – Pubblicato su Cose Antiche n. 193 febbraio 2009 e su ArteVitae.it 22 ottobre 2018 –

© Le foto sono state reperite da libri e cataloghi d’asta o in rete e possono essere soggette a copyright. L’uso delle immagini e dei video sono esclusivamente a scopo esplicativo. L’intento di questo blog è solo didattico e informativo. Qualora la pubblicazione delle immagini violasse eventuali diritti d’autore si prega di volerlo comunicare via email a info@giusybaffi.com e saranno prontamente rimosse oppure citato il copyright ©.

© Il presente sito https://www.giusybaffi.com/ non è a scopo di lucro e qualsiasi sfruttamento, riproduzione, duplicazione, copiatura o distribuzione dei Contenuti del Sito per fini commerciali è vietata.

© The photos have been sourced from books, auction catalogs, or online and may be subject to copyright. The use of images and videos is solely for explanatory purposes. The intent of this blog is purely educational and informational. If the publication of images were to violate any copyright, please communicate this via email to info@giusybaffi.com, and they will be promptly removed or the copyright © will be cited.

© The present website https://www.giusybaffi.com/ is not for profit, and any exploitation, reproduction, duplication, copying, or distribution of the Site’s Content for commercial purposes is prohibited