LA CITTA’ DEL ‘900 ITALIANO – In bilico tra pittura e architettura – THE CITY OF THE 20th CENTURY ITALIAN – Balancing between Painting and Architecture

Milano è sempre stata un laboratorio di modernità soprattutto tra la fine dell’800 e i primi del ‘900, un luogo dove tutte le riflessioni sulla “Nuova Città” immaginata e raccontata per la prima volta dagli artisti del movimento futurista trovano concretezza e realizzazione.

Milan has always been a laboratory of modernity, especially between the late 19th century and the early 20th century, a place where all the reflections about the “New City,” envisioned and narrated for the first time by the artists of the Futurist movement, find concreteness and realization.

Non sarebbe sbagliato affermare che il movimento futurista sia nato a Milano in Via Senato 2, nella casa dove abitava Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

RUSSOLO – CARRA’- MARINETTI – BOCCIONI – SEVERINI a Parigi per l’inaugurazione della prima mostra del 1912 (foto web)

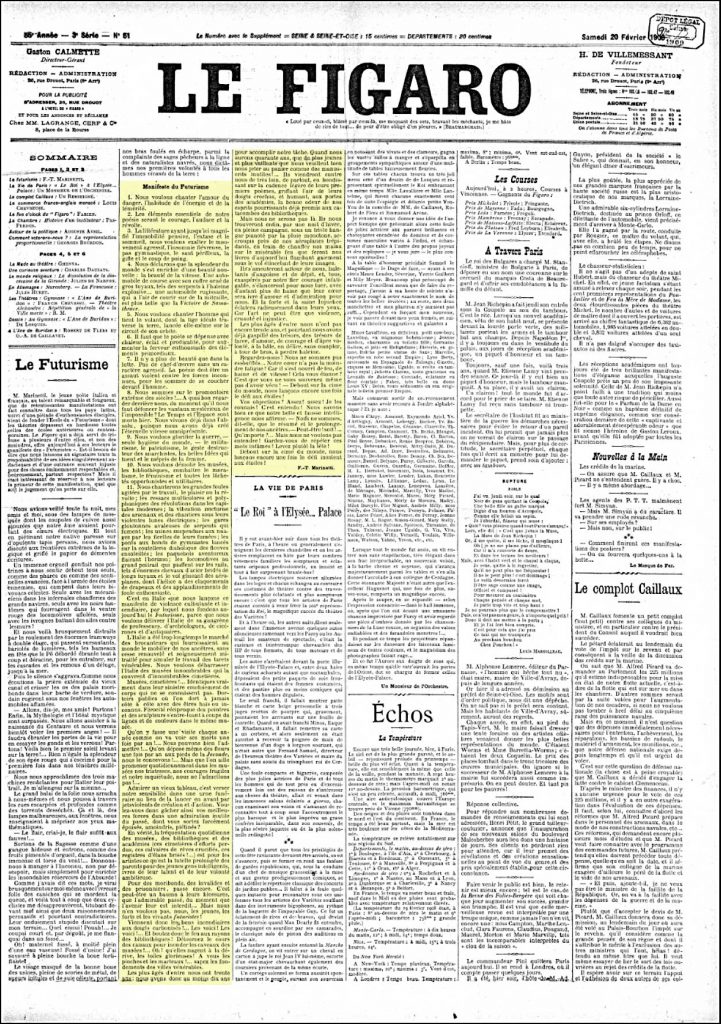

A questo proposito è interessante citare ciò che scrisse Marinetti nel suo Manifesto del 1909 – e pubblicato in Francia sul quotidiano Le Figaro – sul concetto di città:

“Noi canteremo le grandi folle agitate dal lavoro, dal piacere o dalla sommossa: canteremo le maree multicolori e polifoniche delle rivoluzioni nelle capitali moderne; canteremo il vibrante fervore notturno degli arsenali e dei cantieri, incendiati da violente lune elettriche; le stazioni ingorde, divoratrici di serpi che fumano; le officine appese alle nuvole per i contorti fili dei loro fumi; i ponti simili a ginnasti giganti che scavalcano i fiumi, balenanti al sole con un luccichio di coltelli; i piroscafi avventurosi che fiutano l’orizzonte, e le locomotive dall’ampio petto, che scalpitano sulle rotaie, come enormi cavalli d’acciaio imbrigliati di tubi, e il volo scivolante degli aeroplani, la cui elica garrisce al vento come una bandiera e sembra applaudire come una folla entusiasta.”

It would not be wrong to assert that the Futurist movement was born in Milan at Via Senato 2, in the house where Filippo Tommaso Marinetti lived.

In this regard, it’s interesting to quote what Marinetti wrote in his 1909 Manifesto – published in the French newspaper Le Figaro – about the concept of the city:

“We will sing of great crowds stirred by work, by pleasure, or by riot; we will sing of the multi-colored and polyphonic tides of revolutions in the modern capitals; we will sing of the vibrant nocturnal fervor of arsenals and shipyards, ablaze with violent electric moons; greedy railway stations devouring smoking serpents; factories suspended from the clouds by the twisted threads of their smoke; bridges like gymnastic giants that leap over rivers, flashing in the sun like knives; adventurous steamships sniffing at the horizon, and locomotives with wide chests, stamping on the rails like enormous steel horses harnessed with pipes, and the gliding flight of aeroplanes, whose propeller squeals in the wind like a flag and seems to applaud like an enthusiastic crowd.”

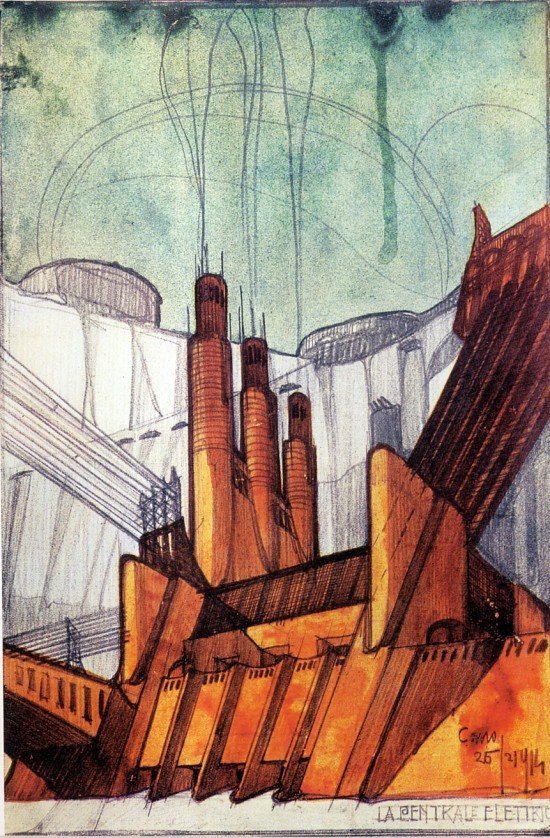

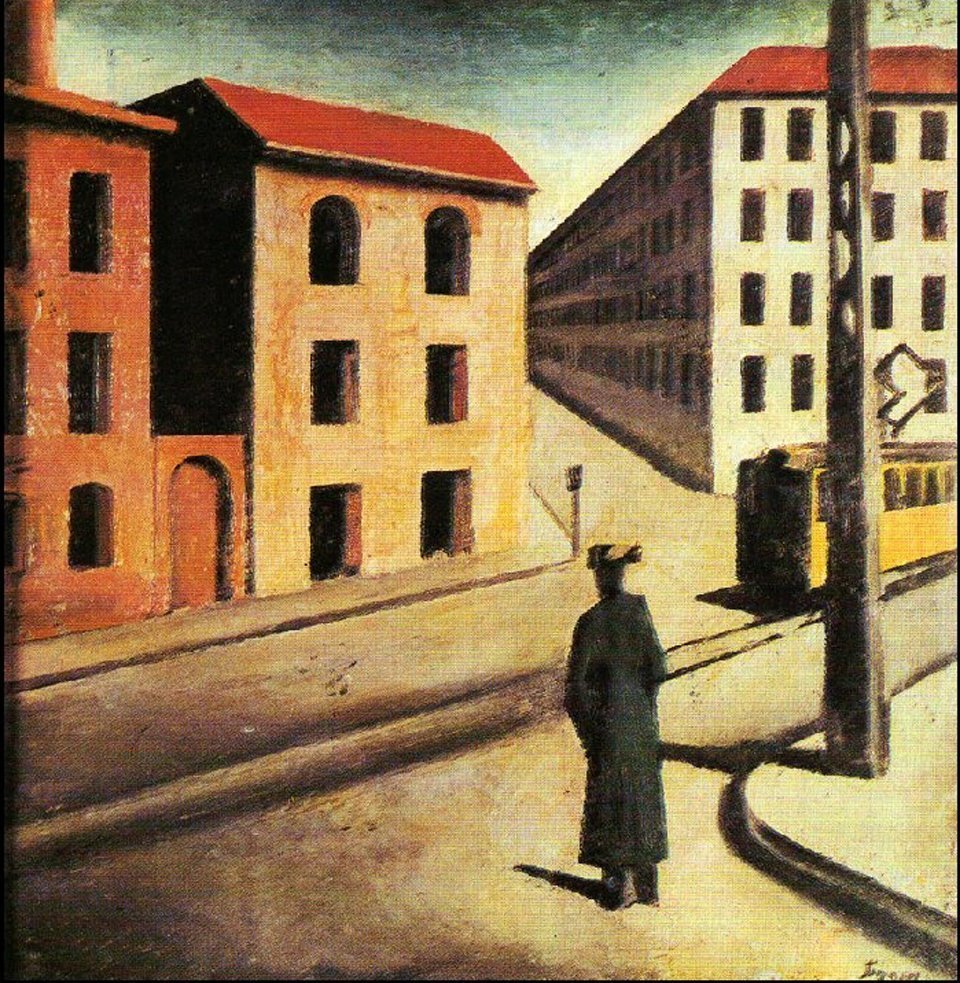

Una città dinamica, che vive una tensione di progresso, che porta una visione di luce elettrica, di mezzi di trasporto, di officine, di locali pubblici. Proprio la luce elettrica diventa il simbolo della nuova città contemporanea, la nuova icona.

A dynamic city, living with a tension of progress, carrying a vision of electric light, transportation means, workshops, and public spaces. Indeed, electric light becomes the symbol of the new contemporary city, the new icon.

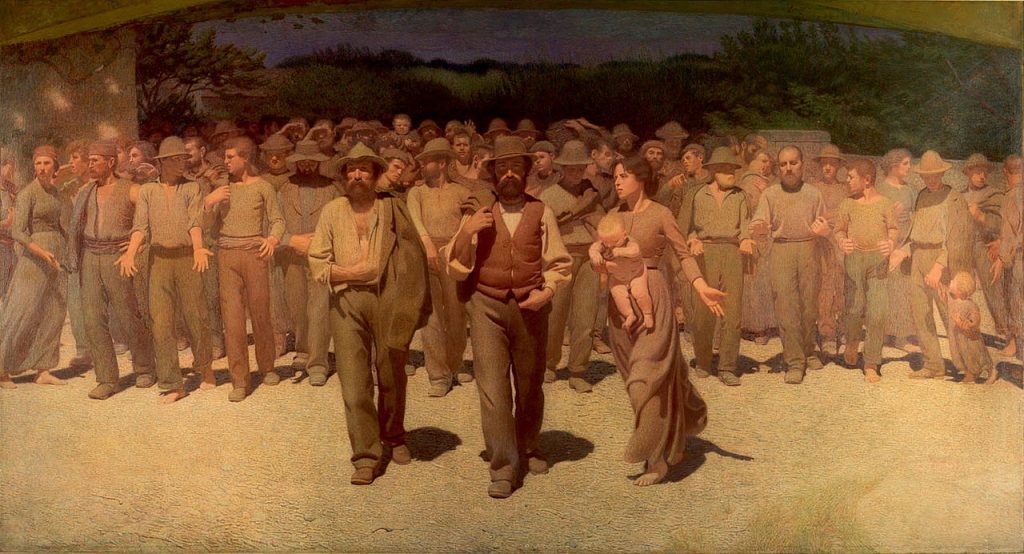

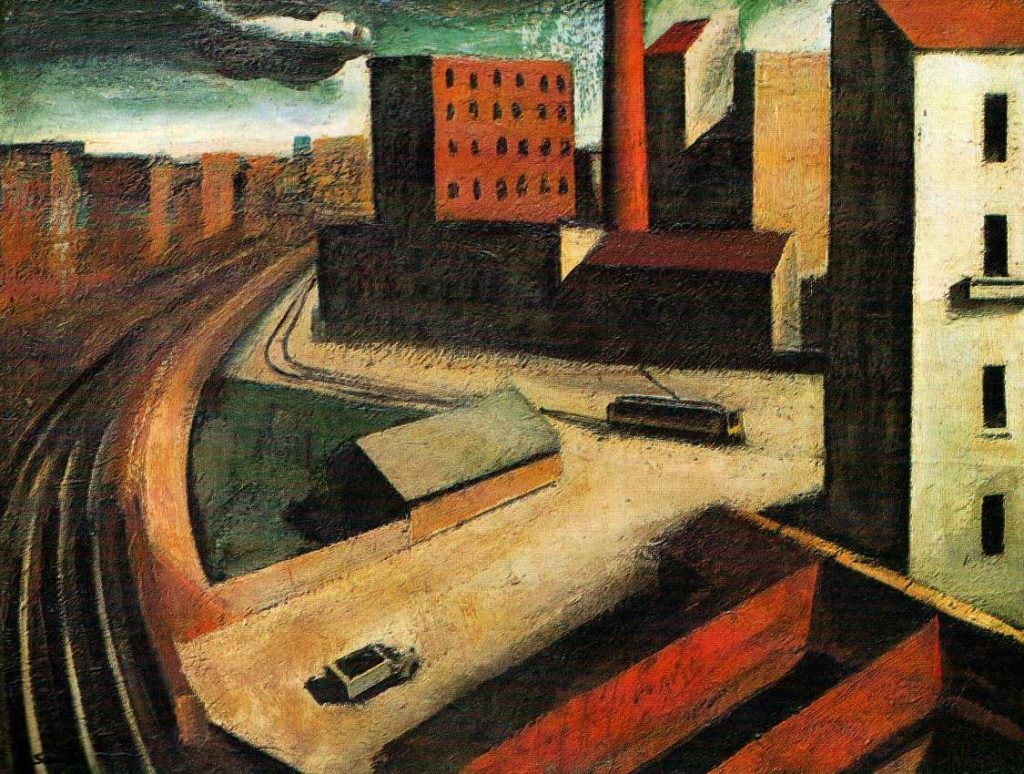

Nascono i nuovi quartieri, destinati ad accogliere i contadini urbanizzati, lavoratori dei campi che vengono attratti in città dal sorgere dei primi impianti industriali.

New neighborhoods emerge, intended to welcome urbanized peasants, field workers drawn to the city by the rise of the first industrial installations.

Corso Lodi di Milano, con il dipinto “Officine di Porta Romana” di Boccioni, benché ancora in stile divisionista, è lo scenario di uno dei primi quadri italiani raffiguranti la città con i grandi palazzi e le ciminiere fumanti.

Corso Lodi in Milan, with the painting “Officine di Porta Romana” by Boccioni, although still in the divisionist style, is the setting of one of the earliest Italian paintings depicting the city with tall buildings and smoking chimneys.

E sempre Boccioni, con il dipinto “La città che sale” entra in pieno nel concetto futurista di dinamicità anche da un punto di vista linguistico, con la forza dei cavalli imbizzarriti in relazione con i palazzi sullo sfondo.

And once again, Boccioni, with the painting “La città che sale” (The City Rises), fully embraces the Futurist concept of dynamism, even from a linguistic perspective, with the power of the wild horses in relation to the buildings in the background.

Ma se gli edifici di Boccioni sono edifici classici, il futurismo aveva in sé qualcosa di molto più visionario, qualcosa che vedremo realizzato cento anni dopo.

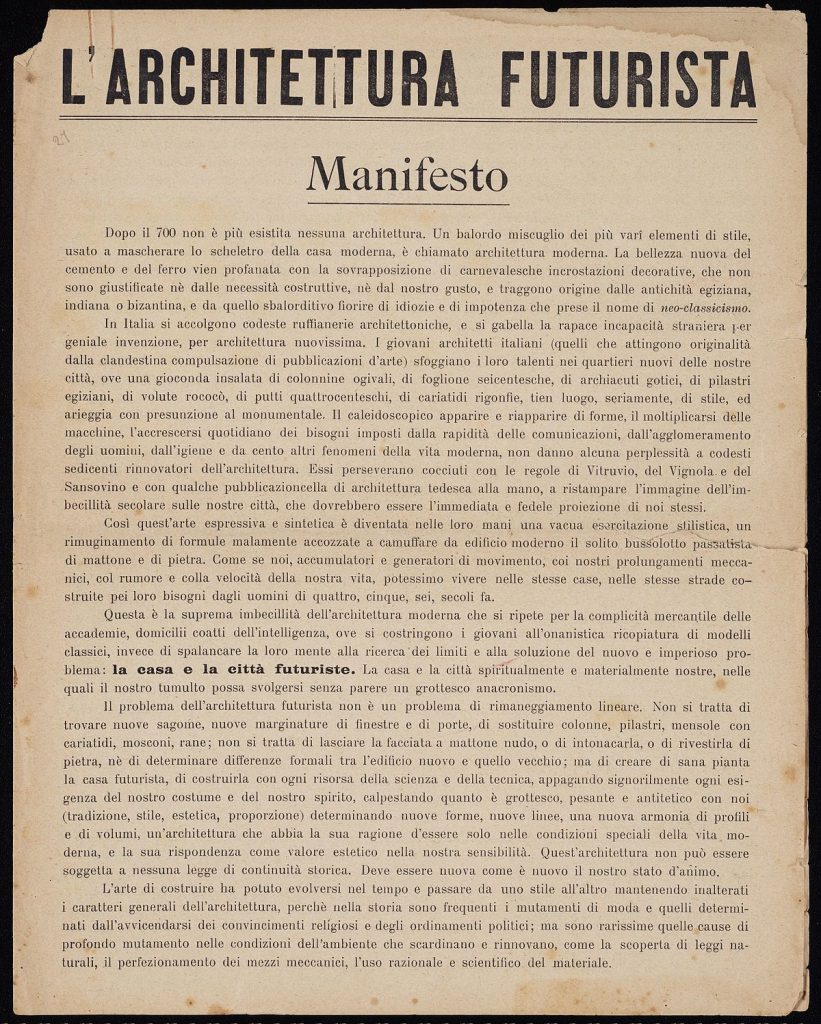

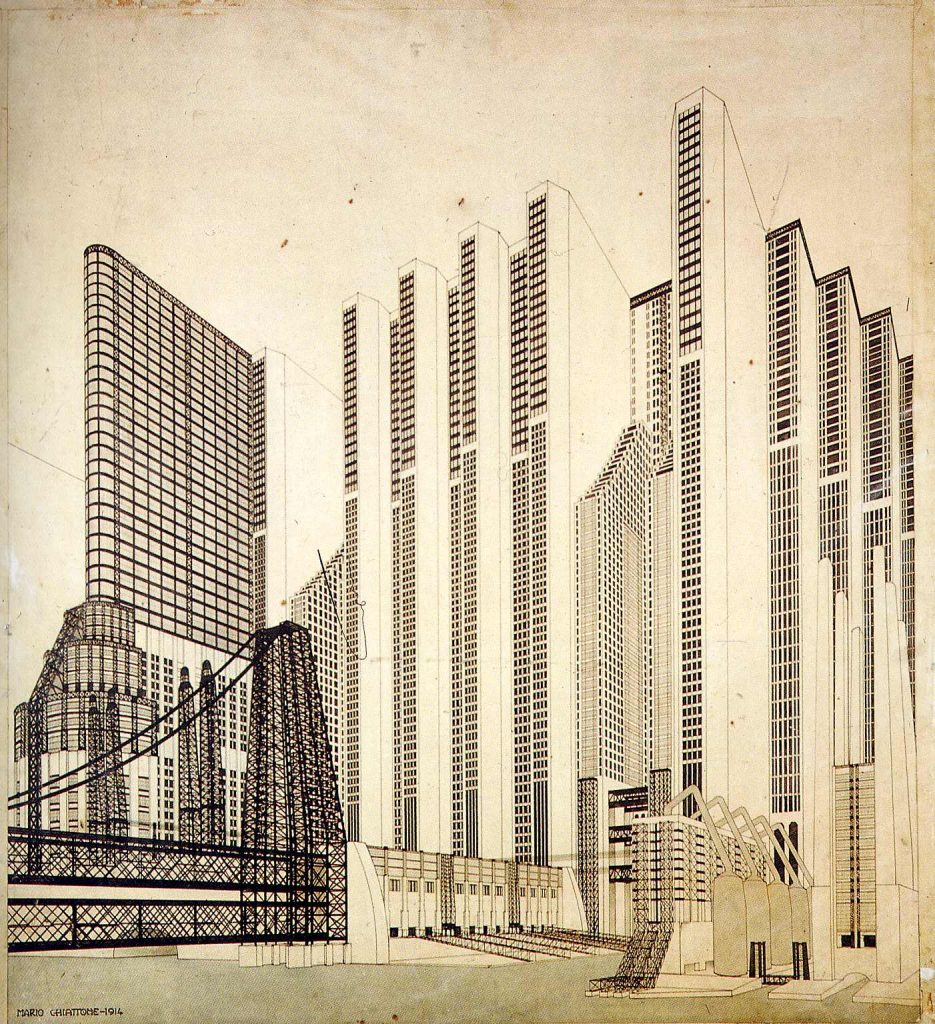

Era il 1914 quando un architetto, Antonio Sant’Elia (1888-1916), scrisse il Manifesto dell’Architettura Futurista, in questo declamava:

“Noi dobbiamo inventare e rifabbricare la città futurista simile ad un immenso cantiere tumultuante, agile, mobile, dinamico in ogni sua parte, e la casa futurista simile ad una macchina gigantesca. Gli ascensori non debbono rincantucciarsi come vermi solitari nei vani delle scale; ma le scale, divenute inutili, devono essere abolite e gli ascensori devono inerpicarsi, come serpenti di ferro e di vetro, lungo le facciate. La casa di cemento di vetro di ferro senza pittura e senza scultura, ricca soltanto della bellezza congenita alle sue linee e ai suoi rilievi, straordinariamente brutta nella sua meccanica semplicità, alta e larga quanto più è necessario, e non quanto è prescritto dalla legge municipale deve sorgere sull’orlo di un abisso tumultuante: la strada, la quale non si stenderà più come un soppedaneo al livello delle portinerie, ma si sprofonderà nella terra per parecchi piani, che accoglieranno il traffico metropolitano e saranno congiunti per i transiti necessari, da passerelle metalliche e da velocissimi tapis roulants .”

But if Boccioni’s buildings were classical, Futurism contained something much more visionary within itself, something that we would see realized a hundred years later.

It was in 1914 when an architect, Antonio Sant’Elia (1888-1916), wrote the Manifesto of Futurist Architecture, in which he proclaimed:

“We must invent and rebuild the Futurist city like an immense and tumultuous construction site, agile, mobile, dynamic in every part, and the Futurist house like a gigantic machine. Elevators should not hide away like solitary worms in staircases; instead, the staircases, rendered useless, must be abolished, and elevators must climb, like serpents of iron and glass, along the facades. The house of concrete, glass, and iron, without paint and sculpture, rich only in the inherent beauty of its lines and reliefs, extraordinarily ugly in its mechanical simplicity, tall and wide as necessary, not as dictated by municipal law, must rise on the edge of a tumultuous abyss: the road, which will no longer spread out like a subordinate at the level of the gatehouses, but will plunge into the earth for several levels, welcoming metropolitan traffic and being connected for necessary transitions by metal walkways and very fast moving walkways.”

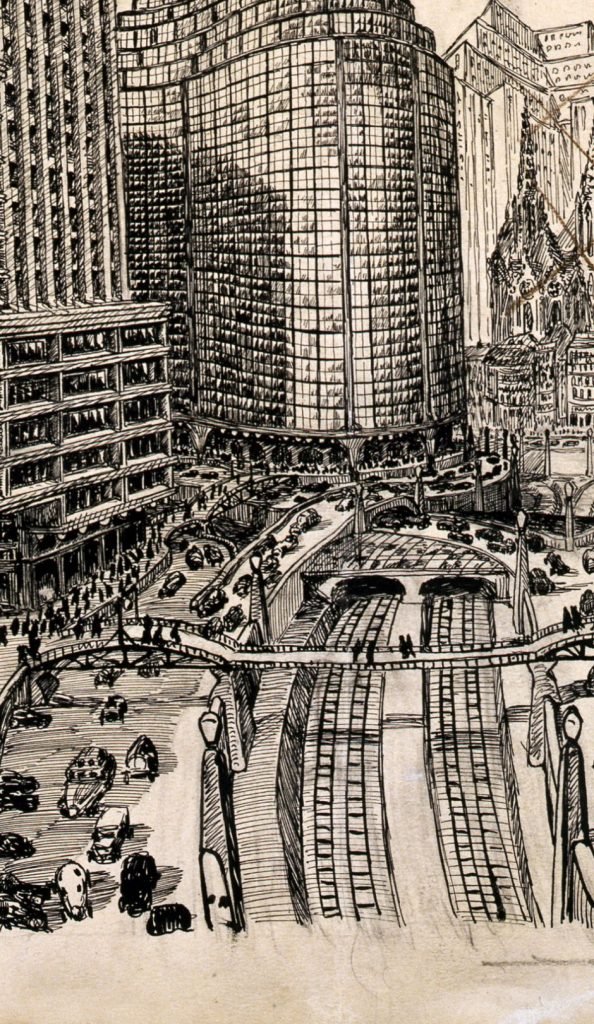

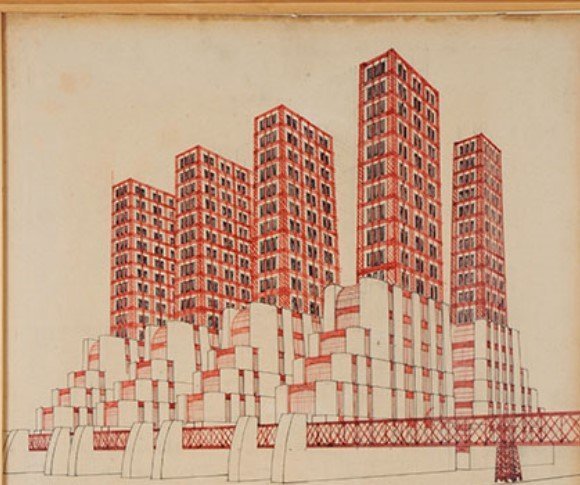

Insieme al suo amico Mario Chiattone (1891-1957) progettano città, anzi metropoli totalmente visionarie per l’epoca, siamo nel 1914, a Milano ci sono i tram a cavallo, il cinema è muto e sta per scoppiare la prima guerra mondiale. Eppure loro progettano alti palazzi, con gli ascensori esterni in modo da “ammirare il panorama”, torri, sottopassi, aree pedonali contrapposte alle strade dove passano le automobili, passerelle di metallo, gallerie, enormi prese d’aria. Idee che lasciano senza fiato, un concetto innovativo di città assolutamente moderna che si sta realizzando solo oggi, cento anni dopo. Architetti che hanno saputo anticipare le intuizioni urbanistiche di questo nostro nuovo millennio.

Together with his friend Mario Chiattone (1891-1957), they designed cities, or rather, metropolises that were completely visionary for their time. This was in 1914, when horse-drawn trams were in Milan, cinema was silent, and the world was on the brink of the First World War. Yet, they designed tall buildings with external elevators for “admiring the panorama,” towers, underpasses, pedestrian areas opposing the streets for cars, metal walkways, galleries, and massive air intakes. Their ideas are breathtaking, representing an innovative concept of an utterly modern city that is only being realized today, a hundred years later. These architects managed to anticipate the urban insights of our new millennium.

Mentre la città di Sant’Elia è esaltata dal concetto del movimento, la città di Chiattone è concepita come un enorme agglomerato urbano, evidenziando la necessità di ridurre le distanze tra abitazioni e luoghi di lavoro.

While Sant’Elia’s city is exalted by the concept of movement, Chiattone’s city is conceived as a massive urban agglomeration, emphasizing the need to reduce distances between residences and workplaces.

Per entrambi gli architetti non è utopia e neanche per noi lo è, anzi è la realtà attuale, anche se in ritardo di cento anni.

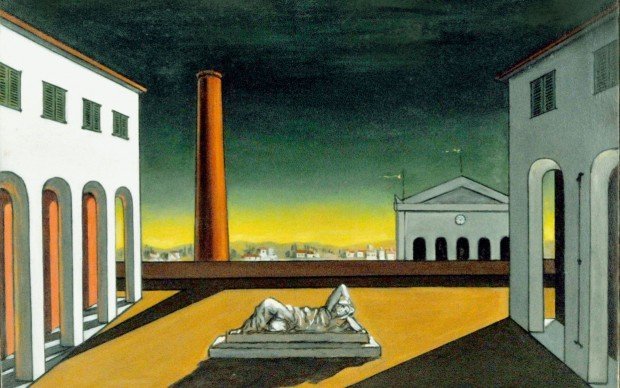

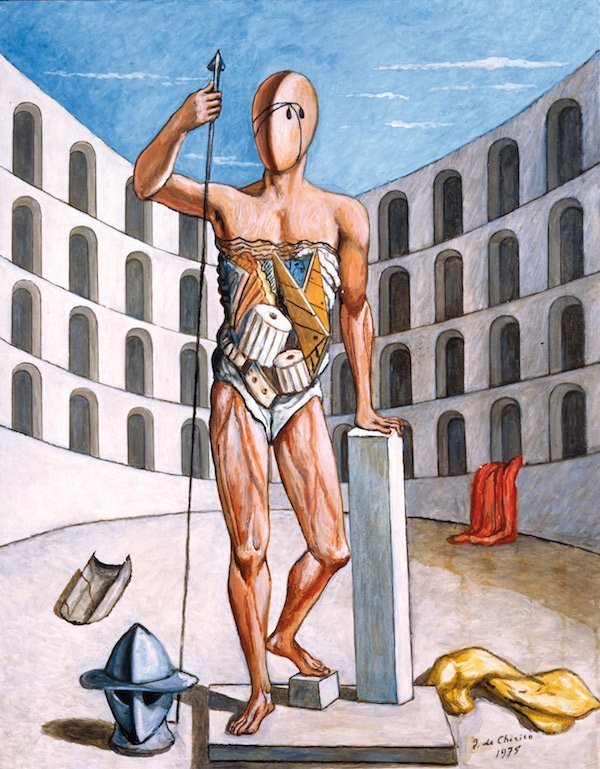

Contemporaneamente, intorno a questa città colorata, caotica, vivacissima dei futuristi, si delinea, nell’arte italiana, un’altra città agli antipodi, silenziosa, vuota, una città che ha avuto più riverbero nell’architettura razionalista, soprattutto nell’epoca del regime: la città immaginata da De Chirico.

La città metafisica è, all’opposto della città futurista, immobile, silenziosa, ordinata, le cui presenze umane sono rare, spesso distanti, ferme, a volte sono solo ombre.

Senza la scoperta del passato, non è possibile la scoperta del presente – Giorgio De Chirico

La città metafisica di De Chirico ha rimandi classicisti, rinascimentali, dove le piazze e i monumenti diventano testimoni di un mondo onirico.

For both architects, it is not utopia, and neither is it for us; in fact, it is the current reality, albeit a century delayed.

Simultaneously, amidst the vibrant, chaotic, and colorful city of the Futurists, another city emerges in Italian art, contrasting in nature—quiet, empty, a city that had a greater influence on rationalist architecture, especially during the era of the regime: the city envisioned by De Chirico.

The metaphysical city stands in stark contrast to the Futurist city; it is motionless, silent, orderly, with rare human presence, often distant, still, and sometimes mere shadows.

“Without the discovery of the past, the discovery of the present is not possible.” – Giorgio De Chirico

De Chirico’s metaphysical city holds references to classicism and the Renaissance, where squares and monuments become witnesses to a dreamlike world.

Sotto questo aspetto la città metafisica non è in alcun modo una città rassicurante, anzi paradossalmente è più avvolgente la città futurista con i suoi tram, la sua gente, la sua folla, le sue luci elettriche, la città metafisica è estraniante, come affermava il poeta francese Jean Cocteau: ”La Metafisica agisce come un assassino che vuole colpirci a tradimento: prima ci tranquillizza, rassicurandoci con soggetti apparentemente famigliari, poi ci ferisce mortalmente, trasportandoci in mondi inquieti e stranianti”

In this regard, the metaphysical city is in no way reassuring; paradoxically, it’s the Futurist city that appears more enveloping with its trams, people, crowds, electric lights. The metaphysical city is alienating, as the French poet Jean Cocteau stated: “Metaphysics acts like a murderer who wants to strike us treacherously: first, it reassures us by presenting seemingly familiar subjects, and then it mortally wounds us by transporting us into restless and unsettling worlds.”

“Ogni cosa ha due aspetti: uno corrente, quello che vediamo quasi sempre e che vedono gli uomini in generale, l’altro spettrale o metafisico che non possono vedere che rari individui in momenti di chiaroveggenza e di astrazione metafisica, così come certi corpi occultati da materia impenetrabile ai raggi solari non possono apparire che sotto la potenza di luci artificiali quali sarebbero i raggi X”. – Giorgio De Chirico

“Everything has two aspects: a current one, which we almost always see and which is seen by people in general, and the other spectral or metaphysical one, which can only be seen by rare individuals in moments of clairvoyance and metaphysical abstraction, just as certain bodies concealed by matter impermeable to sunlight can only appear under the power of artificial lights such as X-rays would be.” – Giorgio De Chirico

De Chirico cavalca l’onda di un cambiamento che è già nell’aria, un’onda che verrà ripresa dagli architetti del regime ed anche in periodi successivi, ma, come per i futuristi che esaltano degli aspetti della realtà precorrendo i tempi, in nessuno dei due mondi la città è completamente reale; frenetica quella futurista, rarefatta quella metafisica.

Le periferie di Sironi corrispondono ad un concetto di solitudine della città, la sua proiezione è quella che noi percepiamo maggiormente, è la metropoli con i suoi lati oscuri.

De Chirico rides the wave of a change that is already in the air, a wave that will be picked up by the architects of the regime and even in subsequent periods. However, just as the Futurists exalt certain aspects of reality ahead of their time, in neither of these two worlds is the city entirely real; the Futurist city is frenetic, while the metaphysical one is rarefied.

Sironi’s outskirts correspond to a concept of the city’s solitude, its projection is what we perceive the most – the metropolis with its darker sides.

Il momento degli anni ’20 che coincide con l’Art Déco, segna un cambiamento sostanziale del costume, del modo di vivere, cambia il concetto abitativo e di vita quotidiana in questa nuova città, di cui Milano è un esempio sorprendente. In Italia, sia negli anni ’20 che ora, Milano è veramente la metropoli cosmopolita per eccellenza dal punto di vista delle dinamiche sociali ma anche urbanistiche, che l’arte ha immaginato, rielaborato e interpretato.

The era of the 1920s, coinciding with Art Deco, marks a substantial change in fashion, lifestyle, and the concept of living. It alters the notions of living and daily life in this new city, of which Milan is a remarkable example. In Italy, both in the 1920s and now, Milan truly stands as the quintessential cosmopolitan metropolis from both social and urban perspectives – a city that art has imagined, reworked, and interpreted.

©Giusy Baffi 2019 (pubblicato su www.artevitae.it – 14 Gennaio 2019)

©Giusy Baffi 2023

© Le foto sono state reperite da libri e cataloghi d’asta o in rete e possono essere soggette a copyright. L’uso delle immagini e dei video sono esclusivamente a scopo esplicativo. L’intento di questo blog è solo didattico e informativo. Qualora la pubblicazione delle immagini violasse eventuali diritti d’autore si prega di volerlo comunicare via email a info@giusybaffi.com e saranno prontamente rimosse oppure citato il copyright ©.

© Il presente sito https://www.giusybaffi.com/ non è a scopo di lucro e qualsiasi sfruttamento, riproduzione, duplicazione, copiatura o distribuzione dei Contenuti del Sito per fini commerciali è vietata.

© The photos have been sourced from books, auction catalogs, or online and may be subject to copyright. The use of images and videos is solely for explanatory purposes. The intent of this blog is purely educational and informational. If the publication of images were to violate any copyright, please communicate this via email to info@giusybaffi.com, and they will be promptly removed or the copyright © will be cited.

© The present website https://www.giusybaffi.com/ is not for profit, and any exploitation, reproduction, duplication, copying, or distribution of the Site’s Content for commercial purposes is prohibited.

ndr: un ringraziamento particolare a Davide Colagiacomo e Osvaldo Ghirardi per la concessione delle loro foto. A special thanks to Davide Colagiacomo and Osvaldo Ghirardi for granting the use of their photographs.