SHUNGA, la stampa erotica giapponese tra il 1600 e il 1800 – Japanese Erotic Prints between 1600 and 1800

«L’ARTE NON E’ CASTA, SE LO FOSSE NON SAREBBE ARTE» Pablo Picasso

“ART IS NOT CHASTE, IF IT WERE SO IT WOULD NOT BE ART” – Pablo Picasso

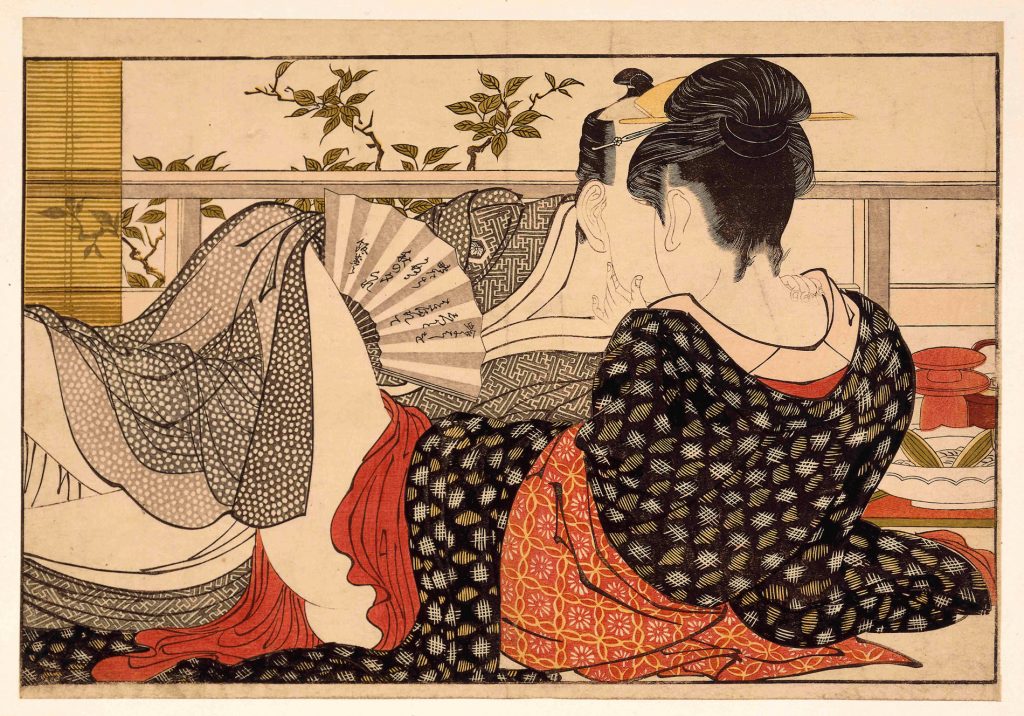

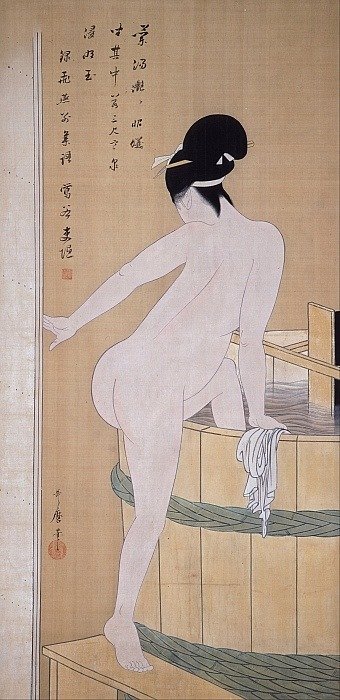

– 1788 – British Museum – Londra

Nella nostra civiltà occidentale si parla molto di arte giapponese in tutte le sue manifestazioni, dalle ceramiche, ai dipinti, ai tessuti, ai paraventi, agli arredi ma si sorvola velocemente, se non addirittura si ignorano volutamente gli Shunga.

Ma di cosa esattamente si tratta?

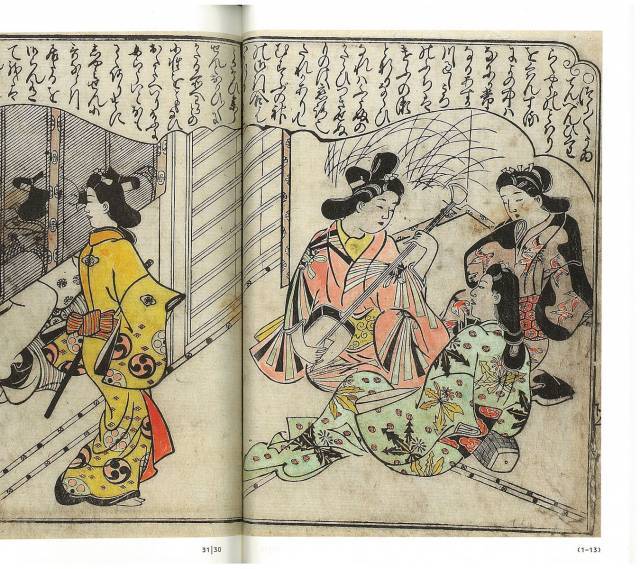

Gli shunga sono dei dipinti, delle xilografie soprattutto, realizzate in Giappone nel periodo EDO (dal nome della capitale, l’odierna Tokyo) detto anche periodo Tokugawa, dal nome della famiglia regnante, che copre un periodo temporale dal 1600 al 1868.

Il termine Shunga tradotto, vuol dire “pittura della primavera”, un modo delicato e poetico per definire l’atto sessuale. Gli shunga appartengono al genere di stampa Ukiyo-e che significa “immagini del mondo fluttuante”, una forma artistica che fiorì nel periodo EDO nelle città di Edo (Tokyo) Osaka e Kyoto e che si riferisce alla cultura giovane, impetuosa, nuova dell’epoca, una concezione edonistica dell’esistenza in un fluttuare di piaceri per allontanare la malinconia della realtà e del dolore.

Le opere Ukiyo-e erano per lo più realizzate in xilografie, ovvero stampe impresse su blocchi di legno per poi essere riportate su seta o carta in maniera seriale. Inizialmente monocromatiche, vennero in seguito arricchite di colori più o meno sgargianti.

In Western civilization, there is a great deal of discussion about various forms of Japanese art, ranging from ceramics and paintings to textiles, folding screens, and furnishings. However, there is often a swift passing over, or even deliberate ignorance, of Shunga.

But what exactly are Shunga?

Shunga are artworks, primarily woodblock prints, created in Japan during the Edo period (named after the capital, modern-day Tokyo), also known as the Tokugawa period, spanning from 1600 to 1868.

The term “Shunga” translates to “spring pictures,” which is a delicate and poetic way to refer to sexual acts. Shunga belongs to the Ukiyo-e genre of printmaking, which translates to “pictures of the floating world.” It was an artistic form that flourished during the Edo period in cities like Edo (Tokyo), Osaka, and Kyoto. This art form represented the youthful, impulsive, and new culture of the era—an hedonistic approach to existence that aimed to alleviate the melancholy of reality and pain through a fluctuation of pleasures.

Ukiyo-e works were primarily produced using woodblock prints, where images were carved onto wooden blocks and then transferred onto silk or paper in a serialized manner. Initially monochromatic, these prints were later enriched with more or less vibrant colors.

Caratteristica dello stile Ukiyo-e è l’assenza della prospettiva, la mancanza di ombre unite a minime sfumature di colore.

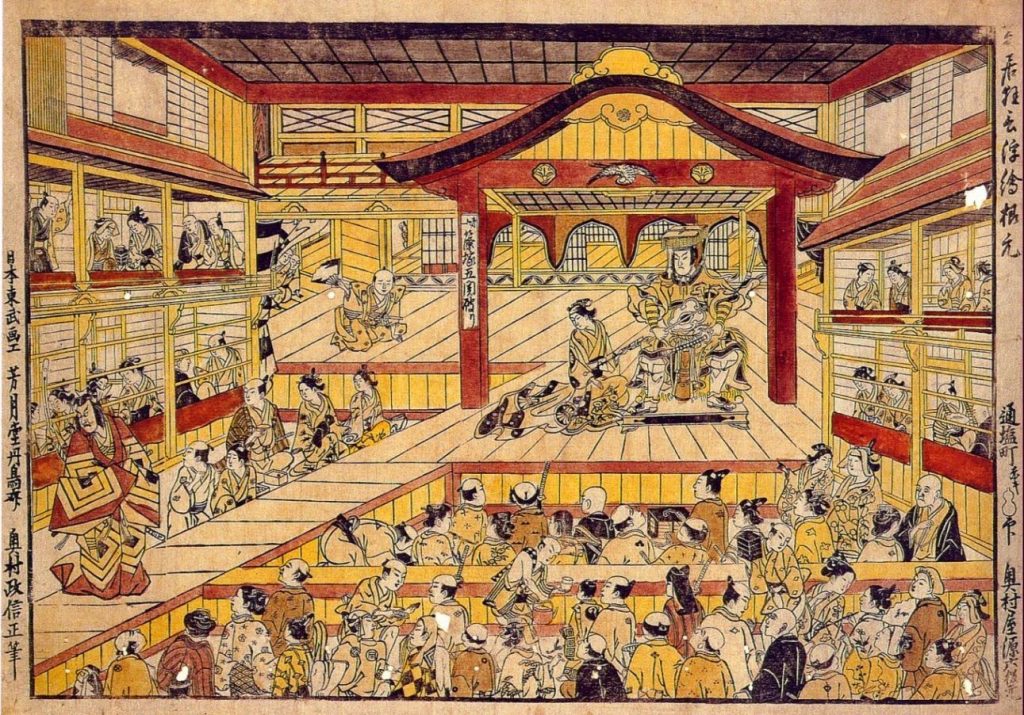

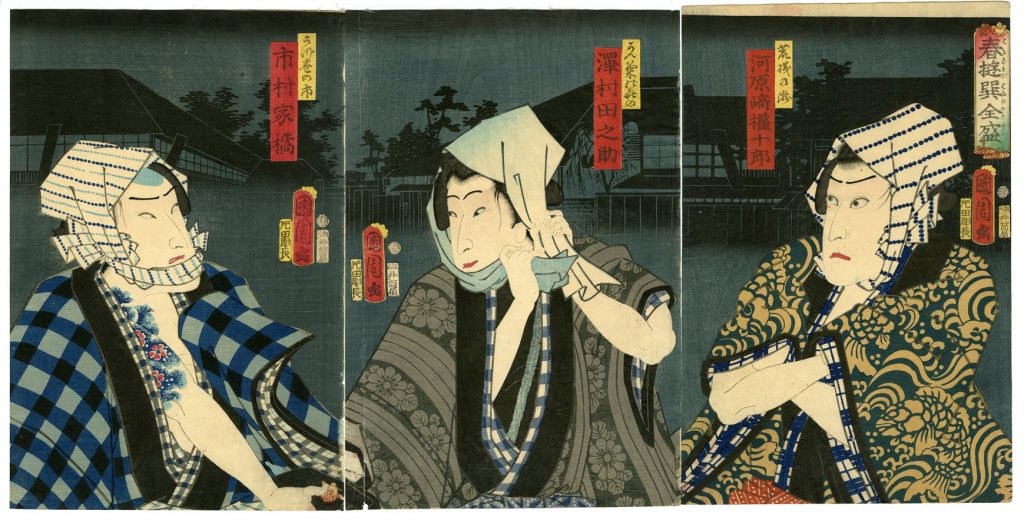

I soggetti erano prevalentemente paesaggi, natura, quartieri, contenuti a carattere erotico e argomenti teatrali con esplicito riferimento al teatro Kabuki, il cui significato si esplica nelle tre parole ka (canto), bu (danza), ki (abilità): espressione artistica dell’epoca, riflesso del pragmatismo della potente ascendente classe mercantile e artigiana degli Chōnin, in netta contrapposizione con la ieratica, compassata alta aristocrazia.

A characteristic of the Ukiyo-e style is the absence of perspective, combined with minimal shading and subtle color gradations.

The subjects predominantly included landscapes, nature, urban scenes, explicit erotic content, and theatrical themes with explicit references to Kabuki theater. The term “Kabuki” derives from the three words “ka” (song), “bu” (dance), and “ki” (skill), reflecting the artistic expression of the era. Ukiyo-e art served as a reflection of the pragmatism of the powerful rising merchant and artisan class known as Chōnin, in stark contrast to the stately and composed high aristocracy.

Libreria Yamada Shoten – Tokyo

Era l’epoca in cui a Edo (Tokyo) stavano avendo sempre maggior successo i quartieri del piacere come Yoshiwara, dove le nuove cortigiane creavano nuovi canoni di gesti e comportamenti con un’eleganza vistosa ed opulenta, basata sull’essere alla moda, sulla difficile arte di attrarre e di respingere al tempo stesso.

Le case di piacere si trasformarono evolvendosi da miseri bordelli in veri e propri salotti dove si incontravano in incognito non solo mercanti ma anche aristocratici, attori, letterati, tutti liberi dal rigore protocollare della loro quotidianità. Proprio in quelle case l’etichetta della seduzione si esprimeva attraverso un canone formale di altissima perfezione e al tempo stesso di naturalezza. Donne maestre nello stile calligrafico, nella composizione floreale e nei segreti dell’amore e della seduzione, cortigiane inaccessibili alla maggior parte della popolazione; solo gli uomini molto ricchi potevano sperare di usufruire dei loro servizi e frequentare le case di piacere.

During this era in Edo (Tokyo), pleasure districts like Yoshiwara were experiencing increasing success. In places like Yoshiwara, new courtesans were shaping new standards of gestures and behaviors with a conspicuous and opulent elegance. This was based on being fashionable and mastering the intricate art of simultaneously attracting and repelling.

These pleasure houses underwent a transformation, evolving from humble brothels into true salons where not only merchants but also aristocrats, actors, and writers met incognito, free from the strict protocols of their daily lives. It was in these establishments that the art of seduction was expressed through a formal canon of utmost refinement while maintaining a sense of naturalness. The women within these houses were skilled in calligraphic style, floral composition, and the secrets of love and seduction. They were courtesans inaccessible to the majority of the population; only the very wealthy men could hope to partake in their services and frequent these pleasure houses.

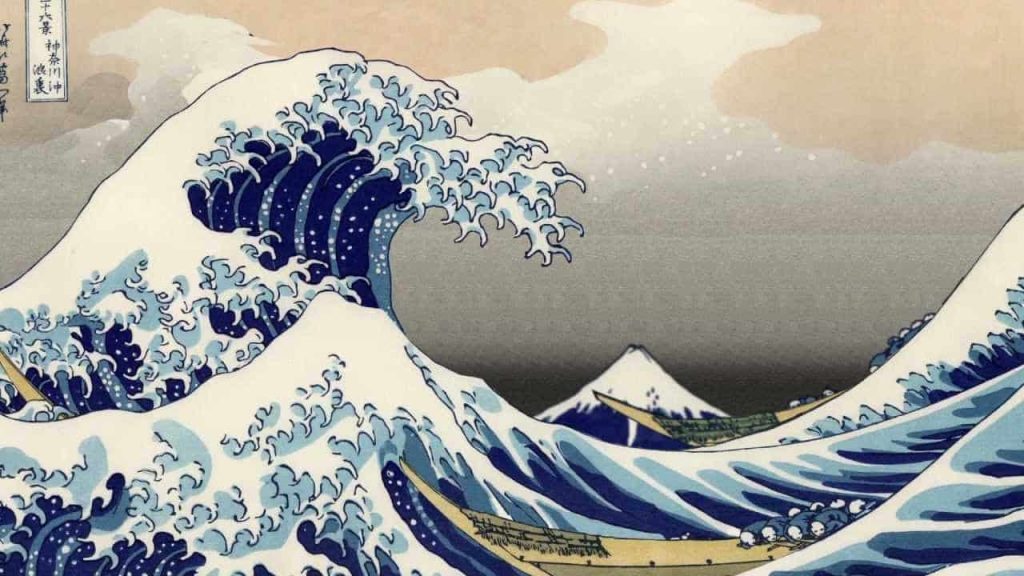

Tra i più importanti esponenti dell’Ukiyo-e troviamo pittori del calibro di Kitagawa Utamaro, Higashisusai Sharaku, Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige e Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

Among the most prominent figures of Ukiyo-e, we find accomplished painters such as Kitagawa Utamaro, Higashisusai Sharaku, Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

Tra il 1760 e il 1790 artisti come Koryusai, Kiyonaga e Shunchō, utilizzano un linguaggio “colto”, ricco di citazioni letterarie dell’epoca, per descrivere l’ideale femminile del loro tempo.

Utamaro stupiva per le raffigurazioni delle cortigiane dai tratti finissimi, con ovali delicati simili a bambole di porcellana, elevandole a icone femminili.

Between 1760 and 1790, artists like Koryusai, Kiyonaga, and Shunchō employed an “elevated” language, rich with literary references of the time, to depict the idealized femininity of their era.

Utamaro was known for his depictions of courtesans with exquisite features, portraying them with delicate ovals reminiscent of porcelain dolls, thereby elevating them to the status of feminine icons.

“Gli Shunga non vivono di inibizioni né da atteggiamenti sessuofobici del cristianesimo o dell’islam, si presentano come un mondo fantastico di gioia sessuale goduto da entrambi i sessi, né il peccato vi trova collocazione. Viceversa subentrano il piacere femminile, la tenerezza e la bellezza” – Carlo Franza – storico e critico d’arte –

“Shunga is not constrained by inhibitions or sexually phobic attitudes from Christianity or Islam. It presents itself as a fantastical realm of sexual joy enjoyed by both genders, devoid of sin. Instead, it highlights female pleasure, tenderness, and beauty.” – Carlo Franza, historian and art critic.

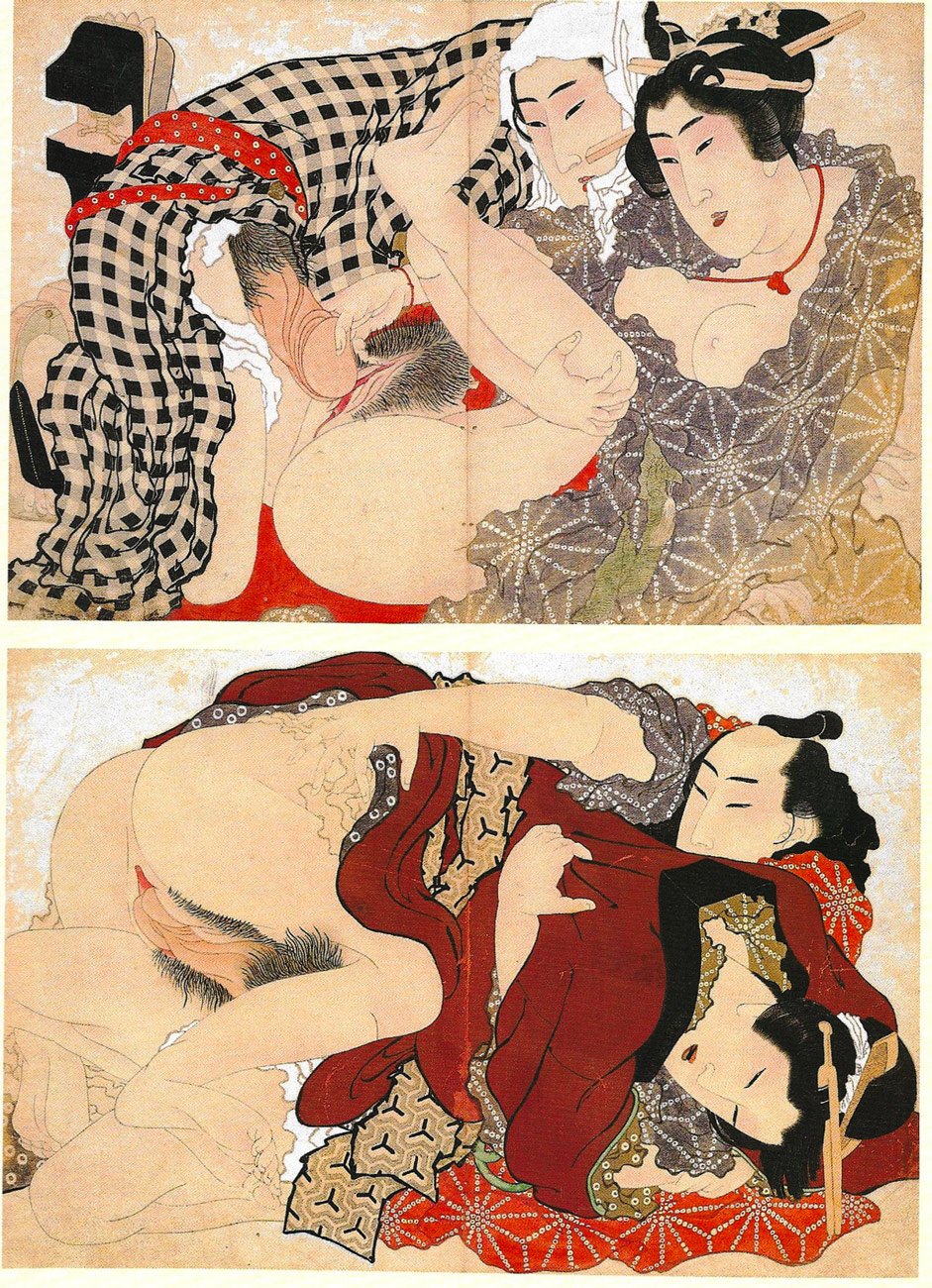

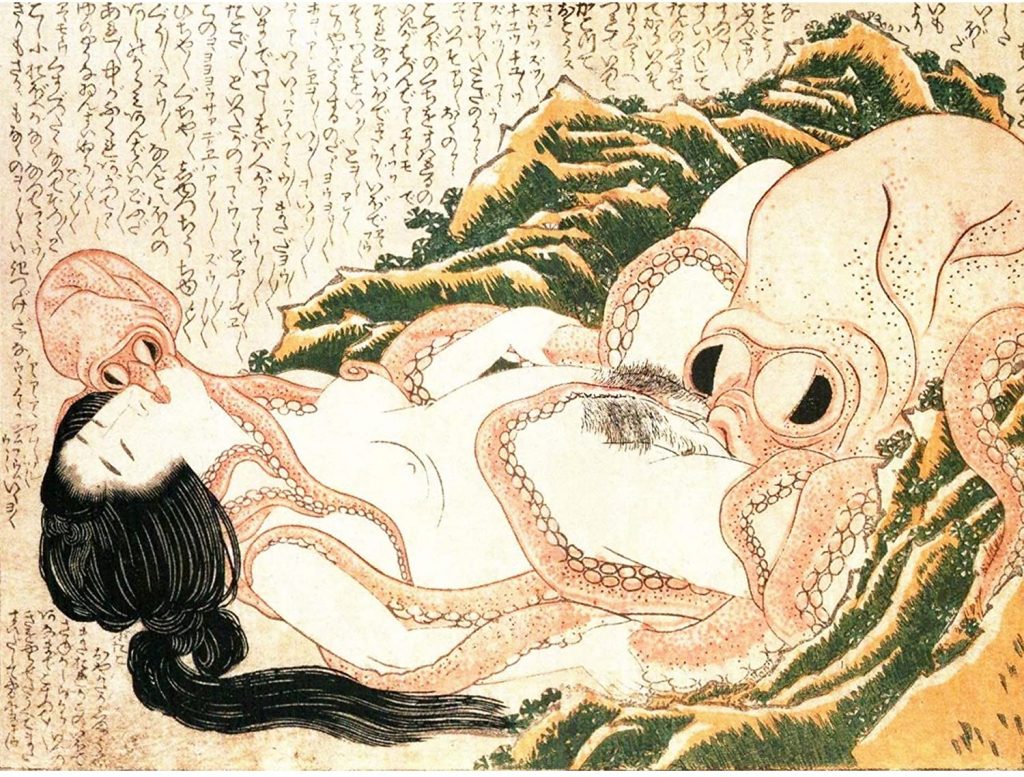

Qualche anno più tardi gli artisti Hokusai, Kunisada e Kuniyoshi, con linee nervose e concitate creavano vivaci campiture cromatiche, inquadrando figure e scene di un erotismo se vogliamo aggressivo precorrendo esteticamente i tratti decadenti della cultura giapponese dell’epoca Meiji.

Questi grandi pittori non avevano nessun problema nel dipingere gli shunga perché per loro, dipingere un’onda piuttosto che un albero o uno shunga era esattamente la stessa cosa, a dimostrazione che l’amore, anche nella sua massima sensualità, assurge ad una sorta di sacralità concepita come un tutt’uno che abbraccia perfettamente il concetto orientale di vita.

Realizzati generalmente in serie di dodici, come i mesi dell’anno, gli Shunga, tramite le immagini, promuovevano una visione positiva del piacere sessuale.

A few years later, artists like Hokusai, Kunisada, and Kuniyoshi, with their dynamic and agitated lines, created vibrant chromatic compositions, framing figures and scenes of what could be called an assertive eroticism. In a way, they were aesthetically foreshadowing the decadent traits of Japanese culture during the Meiji era.

These great painters had no qualms about depicting shunga, as for them, painting a wave, a tree, or a shunga was all the same. This demonstrates that love, even in its most sensual form, is regarded with a kind of sacredness—a unity that perfectly embraces the Eastern concept of life.

Usually created in sets of twelve, mirroring the months of the year, shunga promoted a positive view of sexual pleasure through their images.

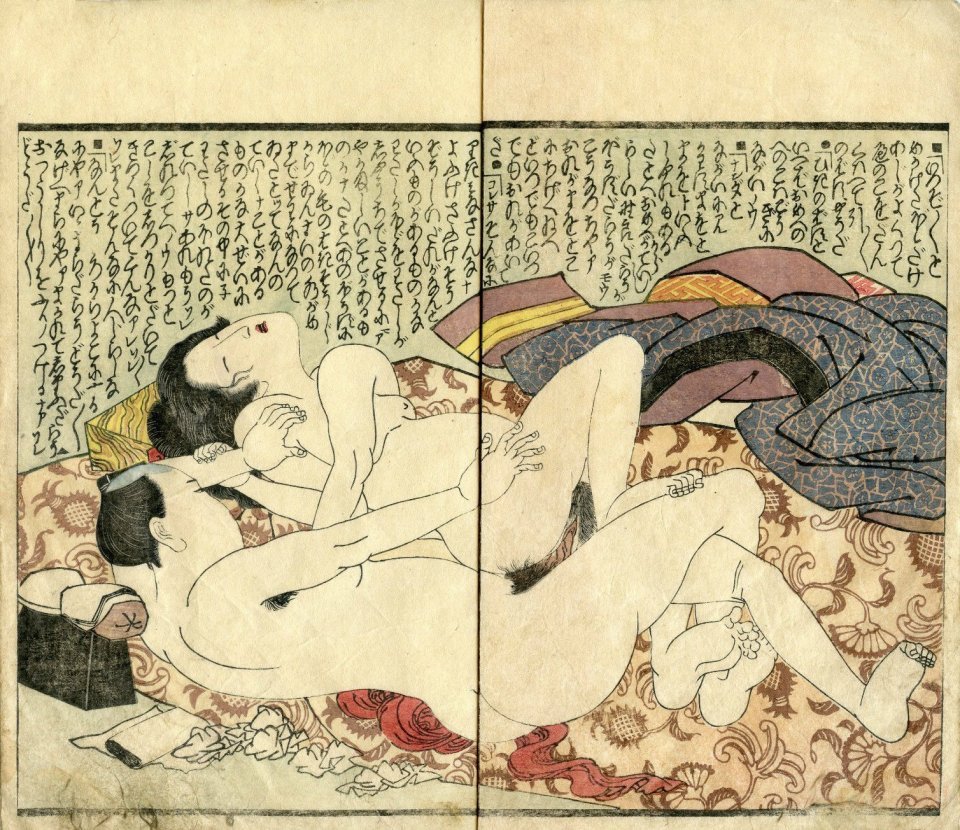

Sono stampe erotiche risalenti fino al 1600, dipinte su seta e spesso in piccolo formato, raramente in rotoli. Gli shunga erano riservati principalmente agli ambienti di corte, ai samurai e destinati anche all’istruzione erotica delle future spose. I protagonisti degli shunga non sono solo cortigiane e i loro clienti, ma anche coppie di sposi o di amanti. Il possedere intere collezioni di opere d’arte shunga era una normale consuetudine anche per le famiglie più rispettabili, custodite come tesori preziosi. Erano anche considerati amuleti contro la sfortuna e le disgrazie.

Gli shunga ci mostrano il concetto di bellezza dell’epoca e del Giappone, in quasi tutti i dipinti i protagonisti sono riccamente vestiti perché era considerato molto più eccitante un piccolo lembo di pelle intravisto tra i tessuti di un kimono che la nudità completa. I genitali vengono appositamente dipinti con una grandezza spropositata rispetto ai personaggi per sottolineare che essi sono i veri protagonisti del dipinto.

These are erotic prints dating back to the 1600s, painted on silk and often in small formats, rarely in scrolls. Shunga were primarily reserved for courtly settings, samurai, and also intended for the erotic education of future brides. The protagonists of shunga are not only courtesans and their clients, but also married or lover couples. Owning entire collections of shunga artworks was a common practice even for the most respectable families, cherished as precious treasures. They were also considered amulets against misfortune and calamities.

Shunga reveal the concept of beauty of the era and of Japan. In almost all the paintings, the protagonists are elaborately clothed, as a small glimpse of skin seen through the fabrics of a kimono was considered much more exciting than complete nudity. Genitals are intentionally depicted disproportionately larger than the characters to emphasize that they are the true focal points of the artwork.

Gli shunga avevano anche una chiara funzione apotropaica nel suo significato più profondo: erotismo uguale a vita, guerra uguale a morte; per questo motivo venivano sempre posti arrotolati nella casse dei samurai quando andavano in guerra, praticamente una sorta di porta-fortuna dell’epoca. Negli shunga, oltre all’erotismo esiste una profonda ricerca pittorica degli abiti, dei tessuti e degli ambienti, in un profondo percorso tanto creativo quanto estetico.

Shunga also had a clear apotropaic function in its deeper meaning: eroticism equals life, war equals death; for this reason, they were always placed rolled up in the chests of samurai when they went to war, essentially serving as a kind of good luck charm of that era. In shunga, beyond the eroticism, there is a profound artistic exploration of clothing, fabrics, and environments, in a profound journey that is both creative and aesthetic.

“[..] è la raffinatezza del tocco pittorico, la grazia infinita dei corpi distesi nel piacere amoroso, che non ci fa percepire alcunché di volgare. Gli artisti Shunga seppero descrivere le espressioni degli amanti con poesia, svuotando la scena di ciò che di animalesco può esserci nell’essere umano, dando la rappresentazione di una sensualità quasi eterea, e perciò molto distante dalla più reale, forse diremmo pornografica, rappresentazione drammatica della sessualità [..]”. Gian Carlo Calza curatore della mostra – Giappone Potere e Splendore 1568/1868 – Palazzo Reale Milano dic. 2009-marzo 2010

“[…] it’s the refinement of the painterly touch, the infinite grace of bodies entwined in the pleasure of love, that prevents us from perceiving anything vulgar. The Shunga artists knew how to depict the expressions of lovers with poetry, emptying the scene of whatever animalistic aspects may reside within the human being, offering a representation of an almost ethereal sensuality, and therefore far removed from the more realistic, perhaps we could say pornographic, dramatic representation of sexuality […].” Gian Carlo Calza, curator of the exhibition – Japan Power and Splendor 1568/1868 – Royal Palace Milan, December 2009-March 2010.

Kuniyoshi, Tsukushi - La diga di Matsu Fuji nel Kyûshû, (1830)

Suzuki Harunobu 1725-1770-Cattiva-condotta-sessuale-dal-libro-Alla-moda-Lusty-Maneemon-libro-stampato-in-legno-inchiostro-e-colore-su-carta-HONOLULU-MUSEUM-OF-ARTS.jpg

Harunobu 1725-1770 Amanti di una veranda Honolulu Museum of Arts .jpg

Utamaro -

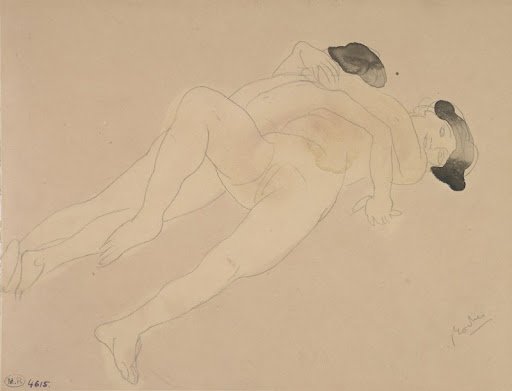

Con i loro tratti delicati, i colori sgargianti dei kimono e gli arabeschi dei corpi avvinghiati, gli shunga hanno notevolmente influenzato anche pittori quali Tolouse Lautrec, Rodin, Egon Schiele, Klimt e Picasso.

With their delicate strokes, vibrant colors of kimonos, and the arabesques of entwined bodies, shunga significantly influenced painters such as Toulouse-Lautrec, Rodin, Egon Schiele, Klimt, and Picasso.

Ne recano l’inconfondibile impronta le incisioni più tarde di Picasso, con Minotauri e modelle impegnati in contorsionistici amplessi, in una versione dell’erotismo sicuramente più colta e raffinata, pare che Picasso acquistò numerose stampe shunga giapponesi, opere dalla linea fine e vigorosa, dai colori sontuosi e stranezze compositive.

The unmistakable imprint of shunga can be seen in Picasso’s later engravings, featuring Minotaurs and models engaged in contortionist embraces, in a version of erotica that is undoubtedly more cultured and refined. It is said that Picasso acquired numerous Japanese shunga prints, works characterized by their fine and vigorous lines, sumptuous colors, and compositional eccentricities.

E’ probabile che Picasso, osservando uno shunga, pensasse. “Non posso dire che se il mio viso è rivolto in questo modo anche i miei piedi non possano essere rivolti nella stessa maniera!”

C’è una teoria secondo cui il cubismo di Picasso (una tecnica per mettere oggetti da varie angolazioni su un unico piano) non sarebbe stato possibile senza gli shunga o “i dipinti di primavera”. In effetti, una mostra è stata organizzata nel 2010 al Museo Picasso in Spagna con il tema di “Picasso e la pittura di primavera”.

It’s likely that Picasso, upon observing a shunga, might have thought, “I can’t say that if my face is turned this way, my feet can’t be turned the same way!” There is a theory that Picasso’s Cubism (a technique to depict objects from various angles on a single plane) wouldn’t have been possible without shunga or “spring paintings.” In fact, an exhibition was organized in 2010 at the Picasso Museum in Spain with the theme “Picasso and the Painting of Spring,” highlighting this connection.

Descrizione delle opere contrassegnate con asterisco * Description of the works marked with an asterisk (*)

1) Hiroshige e Kunisada. – Veduta con la neve -1853 – trittico di ōban – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

2) Kunisada – Eastern Genji: Il giardino innevato (Azuma Genji yuki no niwa) – 1854 – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Bibliografia:

Gian Carlo Calza – Giappone, Potere e Splendore 1568-1868 – Federico Motta Editore 2009

Ringrazio Gianni Crespi per la sua gentile consulenza. Special thanks to Gianni Crespi for his kind advice.

©Giusy Baffi 2020

© Le foto sono state reperite da libri e cataloghi d’asta o in rete e possono essere soggette a copyright. L’uso delle immagini e dei video sono esclusivamente a scopo esplicativo. L’intento di questo blog è solo didattico e informativo. Qualora la pubblicazione delle immagini violasse eventuali diritti d’autore si prega di volerlo comunicare via email a info@giusybaffi.com e saranno prontamente rimosse oppure citato il copyright ©.

© Il presente sito https://giusybaffi.com/ non è a scopo di lucro e qualsiasi sfruttamento, riproduzione, duplicazione, copiatura o distribuzione dei Contenuti del Sito per fini commerciali è vietata.

© The photos have been sourced from books, auction catalogs, or online and may be subject to copyright. The use of images and videos is solely for explanatory purposes. The intent of this blog is purely educational and informational. If the publication of images were to violate any copyright, please communicate this via email to info@giusybaffi.com, and they will be promptly removed or the copyright © will be cited.

© The present website https://giusybaffi.com/ is not for profit, and any exploitation, reproduction, duplication, copying, or distribution of the Site’s Content for commercial purposes is prohibited.